Read an extract from The Mother’s Day Club by Rosie Hendry

Chapter 1

East End, London – 3 September 1939

It was a beautiful late-summer day with a blue sky soaring high above the East End streets and Marianne Archer was in a hurry, her gas mask box banging against her hip and her heavy suitcase making her slower than usual. Her step faltered as she spotted a newspaper billboard set out on the pavement ahead of her and read the bold message printed in stark black and white: ‘Peace or War?’ It made her catch her breath. Would it really come to war?

She’d listened to the wireless, read the newspapers and seen all the preparations going on around London, and she knew full well that the country was teetering on the brink of war, but deep down she’d held on to the hope that somehow, by some miracle, it wouldn’t come to it, and that something would happen even now, at the last minute, to stop it.

Looking up at the sky, which looked so perfect today, without a single cloud to mar the blue, you’d never know what was going on, she thought, never know what chaos was probably about to be unleashed.

Pushing on past the billboard, she followed the stream of people heading to the local school where all evacuees had been instructed to gather. The sight of so many evacuees carrying their luggage through the streets had become a familiar one in the last few days. The children had been the first to go; now it was the turn of the expectant mothers, and Marianne was glad to be leaving, not just because of the threat of war and what it might bring here, but because London had turned sour for her. What had started out as an exciting adventure and blossoming career had gone badly wrong and she was eager for a new start.

Inside the school, she joined the end of the queue of people waiting to register their arrival, relieved to put down her suitcase at last. Looking around her, she saw that the hall was already busy – not just the expectant mothers and young children who were preparing to leave, but also their relatives and even some husbands too, who’d clearly come to see them off. The noise level was rising steadily among the swirl of cigarette smoke, people having to speak ever louder to make themselves heard above the din of chatter, grizzling children and even a few weeping women.

The queue shuffled forwards slowly. The woman ahead of Marianne had to heave her fractious toddler up on to her hip, her swollen stomach making it impossible for her to hold the child in her arms in front of her. Nudging her brown suitcase forward with her foot, Marianne looked down at her own growing belly – it was impossible now to do up more than the top three buttons on her thin summer coat; there was no hiding the fact that she was expecting any more.

‘Next.’ The mother in front of Marianne had been dealt with and moved off, heaving her toddler and string bag of belongings with her. The WVS woman sitting at the desk looked up at Marianne through her round glasses and smiled. ‘Your name?’

‘Marianne Archer.’

She ran her finger down the list, found Marianne’s name and put a tick beside it. ‘If you’d like to take a seat . . . ’ She looked around the hall and shrugged: there wasn’t an empty seat to be had. ‘We weren’t expecting quite so many family members to turn up. We’ll be leaving shortly anyway, so you won’t have long to wait.’

‘All right, thank you.’ Marianne picked up her suitcase and went to stand by the open door where the fresh air, or at least what passed for that around here, was blowing in on a welcome breeze, ruffling her dark brown, shoulder- length wavy hair. She could smell the distinctive tang of the East End – chimney smoke from the many homes and factories combined with a salty twist from the docks and the River Thames. Proper fresh, clean air that didn’t irritate your nose was something she was looking forward to again, along with wide skies, space and greenery. She had lived in London for the past four years, coming to work here when she was sixteen, but the city had never truly felt like home. In fact, Marianne dearly missed the countryside, so now, being evacuated to a place that didn’t have a shop on every corner, buses one after the other, or street after street of terraced houses, would be no hardship for her.

They set off walking through the streets towards Liverpool Street station a short while later, forming a raggle- taggle line behind a WVS evacuation officer in her smart green uniform, who, like a modern- day Pied Piper, was leading them to safety. Many of the evacuees carried luggage that looked inadequate for the journey ahead, their belongings stuffed into string or paper bags, sacks or cardboard boxes; not many of the expectant mothers had a suitcase like Marianne.

As they passed through the streets where some of them lived, the evacuees’ neighbours stood in their front doorways watching them go and calling out tearful farewells.

‘Look after yourself, ducks.’

‘We’ll keep the ’ome fires burning for yer.’

There was a real sense of loss in the air as part of their community was leaving, Marianne thought, looking at the women who were waving them off and wiping their eyes with their spotlessly clean handkerchiefs. The East Enders were a close- knit bunch, sharing their ups and downs, helping each other out, so to have mothers evacuated was like taking the beating heart out of their homes, and they’d be sorely missed by those they left behind.

She couldn’t say the same about herself, though. Her departure was leaving nothing but an empty room behind, and her landlady probably had a new tenant lined up already. There was no one around here to be sad that she was going, but that was the way she’d wanted it. Moving to the East End to work in a clothing factory two months ago and live anonymously had been the best thing to do, but seeing the emotion and heartfelt tears of friends and family saying their goodbyes tugged at her heart and prodded at the loneliness she’d felt since then. Making the best of a situation wasn’t always easy, her gran had often said, but that’s what she’d had to do.

‘Dad says to tell you, Chamberlain says it’s war!’ A boy hurtled out of one of the houses, broadcasting the news as he ran up to one mother just ahead of Marianne, grabbing at her hand. ‘He just said so on the wireless.’

Surprisingly, no one stopped at the momentous news, the formation kept on moving, and although it wasn’t unexpected, the certainty that they were now at war with Germany made Marianne’s heart sink. It was little more than twenty years since the last time they’d been pitched against this enemy, and she’d grown up with the shadow of the last war blighting her life – her father had been killed in the last few months before she was born. She’d heard the stories of the muddy trenches and the huge death toll, seen the men with shattered lives and missing limbs. That had been the war to end all wars, and yet here it was, happening all over again.

The sudden sound of an air- raid siren began to wail out across the rooftops, its eerie cry rising and falling again and again, like some wounded animal. It changed the mood like the flick of a switch, and the formation faltered. People halted, looking up at the sky, their eyes wide in shock. Several mothers began to cry, and toddlers, picking up on the women’s distress, added their own wails.

Marianne looked around her, uncertain what to do. Could the Germans be about to bomb them so soon? A passing red double- decker bus pulled over to the side of the road, the driver and passengers spilling out in panic and quickly disappearing down side streets. Should they do the same?

One of the evacuation officers clapped her hands and shouted, ‘Keep moving!’

‘Don’t stop! We need to get to Liverpool Street,’ another added, working her way down the column encouraging everyone to move off again. They did as they were told; no one questioned it or ran off, but they quickened their pace, adults picking up any toddlers who were too slow, everyone anxious to reach the station and get under cover.

‘You’d best go back, Granddad,’ a young woman near Marianne said to the old man who was accompanying her. ‘If they comes, you can’t run. I can’t let the Nazis catch you.’

‘Curse ’em. I ain’t letting you go alone.’ The old man shook his stick at the sky and kept on walking, doing his best to keep up.

There’d been no sound of aeroplanes approaching or bombs falling, but Marianne still felt hugely relieved when they finally arrived and had the domed roof of Liverpool Street station, with its ornate iron beams, between her and any enemy planes.

‘This way,’ the leading evacuation officer shouted in her loud plummy voice. She led them across the busy station concourse where the air smelt of burning coal from the steam engines, parting the people hurrying to and fro, like Moses had the Red Sea.

As they reached the barrier at platform ten, the steady sound of the all- clear rang out and the atmosphere lightened. They were safe – for now, at least.

‘Evacuees only on the platform,’ another WVS woman called. ‘There isn’t room for everyone so you’ll need to say your goodbyes here.’

Marianne side- stepped the families saying their tearful farewells, grateful now that she didn’t have the emotional wrench of having to leave loved ones behind. Quite the opposite, in fact: she was glad to be going. From the way some of the expectant mothers were clinging to their husbands or relatives, tears streaming down their faces, they didn’t share her feelings.

Walking past the railway guards who stood by the barrier to make sure that no other family members sneaked on to the platform, she headed to the far end of the train that stood ready to take them to safety and climbed aboard a carriage. She chose a compartment, slid open the door, stowed her case and settled herself by the window facing the engine, so she’d be able to enjoy the view as they travelled.

As Marianne waited for the train to fill up, her mind wandered over the possibilities of what lay ahead. She tried to calm the tingle of apprehension that had lodged itself in her chest, visualising what it might be like, who she would be billeted with. She hoped it was someone nice; she’d done her best to look presentable, wearing the new dress she’d designed and made herself with its pin- tuck detail on the bodice, in a beautiful deep green fabric that went well with her green eyes. It was important to make a good first impression – another of her gran’s many sayings. She smiled as she pictured her saying it so many times as she’d grown up, though what she would say about the situation Marianne had got herself into she hardly dared think. Perhaps it was just as well that Gran had passed away a year ago now, because she’d have been bitterly disappointed in her, and that would have been nearly as hard to bear as her own anger at her stupidity and naivety.

‘Excuse me, is that seat taken?’

Marianne was pulled out of her thoughts and looked up to see an auburn- haired young woman standing in the open doorway of the compartment and pointing at the empty seat opposite her. In fact, it was the only empty seat left – while Marianne had been absorbed in her own world, the other seats had filled up with another expectant mother and her two little girls and two other women who had pulled out their knitting and were already busy, their needles clicking.

She smiled at her. ‘No.’

‘Oh, thank Gawd.’ She shuffled past the other occupants’ legs and stuffed her bag of belongings in the overhead luggage rack then plopped herself down on the seat. ‘I’d begun to think I’d ’ave to stand all the way to wherever we’re goin’. The train’s filled up so fast, but I ’ad to stay with my Arthur for as long as I could, and then the WVS woman was chivvyin’ me to get a shift on or the train would go without me.’ She paused for breath and stuck out her hand with a friendly smile. ‘I’m Sally Parker.’

Marianne shook her hand. ‘Marianne Archer.’ She smiled at the other woman, noticing her red- rimmed eyes and pink- tipped nose.

‘Pleased to meet you, Marianne. Are you looking forward to this? Cos I ain’t, but my Arthur said I ’ad to go for the sake of this one.’ She stroked her stomach, which protruded from her slender frame like a football, pushing out the front of her floral dress. ‘He’s going to enlist for the Army right away, not wait to be called up, so he won’t be around here anyway. Did your hubby want you to go too?’

Marianne nodded.

‘He come and see you off?’

‘No.’

‘That’s a shame.’ Sally frowned. ‘Couldn’t he get time off work?’

‘He’s in the Navy, at sea.’ The words tripped awkwardly off Marianne’s tongue.

‘Well, he’ll be glad you’re on your way to safety.’

Marianne nodded, relieved when they were distracted by a sudden loud blast from the guard’s whistle outside. Soon the carriage began to move, the platform slipping past, as the steam engine at the head of the train belched out great chuffs of sooty smoke that swirled up to the ornate station roof.

‘Where do yer think we’re going?’ Sally asked as they cleared the gloom of the station and slipped out into the beautiful sunshine.

Marianne looked at this young woman, who suddenly seemed very vulnerable and nervous in spite of all her chatter. ‘I don’t know, we haven’t been told, but as we’re leaving from Liverpool Street, I’d guess it must be somewhere in the east, not Devon or Wales.’

‘Right out in the countryside, then?’

‘Yes. And away from where they might drop bombs.’

Sally stared out of the window for a few moments. ‘I ain’t been out to the countryside much before, I’ve been ’op picking a couple of times down in Kent, but that’s all.’

‘It will be different from London, but I’m sure it’ll be fine,’ Marianne said. ‘Better to be safe.’

Sally nodded, leaning against the back of her seat. ‘That’s what my Arthur said.’ She rubbed her hand across her stomach. ‘So, when’s yours due? Mine should be ’ere by Christmas.’

‘Late January for me.’

‘Will your husband be home before then to see yer?’ Sally asked. ‘Arthur’s promised to come and visit me when ’e can, though once he’s in the Army it’ll be up to them when he’s allowed.’

‘I’m not sure.’ Marianne looked down at the still- shiny gold ring on the third finger of her left hand. She’d bought it herself.

‘Well, yer can always write letters in the meantime, can’t yer?’ Sally said as they passed row upon row of tightly packed terrace houses.

‘Of course.’

‘My Arthur says he can’t wait to get my first letter . . . ’

Marianne listened to Sally chattering on, the young woman having enough to say for both of them, while the wheels of the train clickety- clacked beneath them. Through the window the streets gradually gave way to more greenery, space and light, and the sight made her heart lift. Wherever they were heading had to be better for her than London had turned out to be.

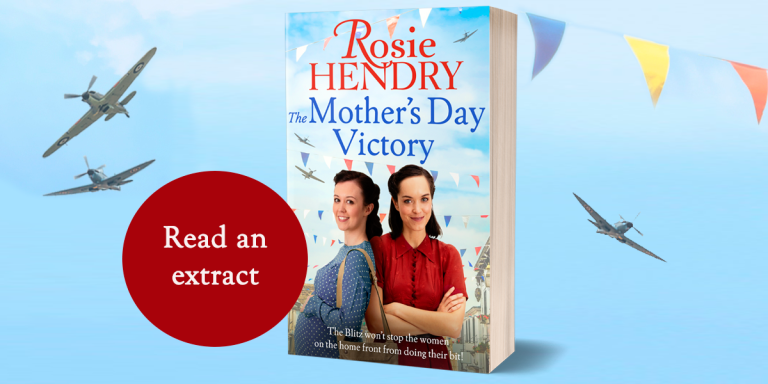

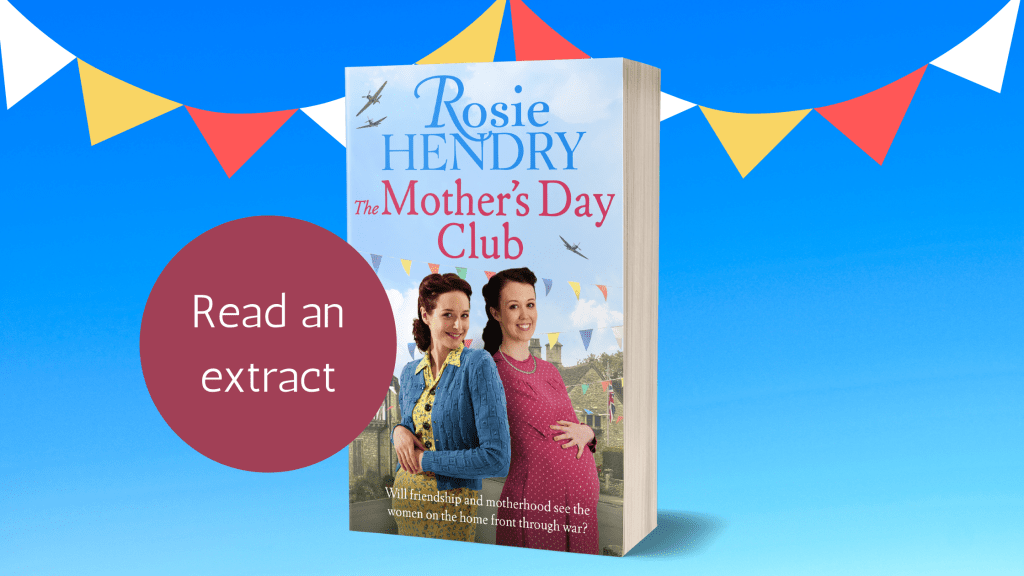

THE BRAND NEW SAGA SERIES BY ROSIE HENDRY - meet the Women on the Home Front . . .

Winner of the 2022 Romantic Novelist Association, Romantic Saga Award

Will friendship and motherhood keep the Women on the Home Front safe from war?

Norfolk, 1939

When the residents of Great Plumstead, a small and charming community in Norfolk, offer to open their homes to evacuees from London, they're expecting to care for children. So when a train carrying expectant mothers pulls into the station, the town must come together to accommodate their unexpected new arrivals . . .

Sisters Prue and Thea welcome the mothers with open arms, while others fear their peaceful community will be disrupted. But all pregnant Marianne seeks is a fresh start for herself and her unborn child. Though she knows that is only possible as long as her new neighbours don't discover the truth about her situation.

The women of Great Plumstead, old and new, are fighting their own battles on the home front. Can the community come together in a time of need to do their bit for the war effort?

The Mother's Day Club is the perfect wartime family saga, filled with heart-warming friendships, nostalgic community spirit and a courageous make-do-and-mend attitude. Perfect for fans of Ellie Dean, Sheila Newberry and Elaine Everest.

Early readers LOVE The Mother's Day Club:

'I highly recommend this book and give it a well-deserved five stars'

'It's books like this that remind me why I love reading . . . I can't wait to read more from Rosie Hendry'

'Fabulous - can't wait to read the next book'

'Beautifully written . . . Thank you to Rosie Hendry for writing this five-star book'

'A fantastic book - highly recommended'