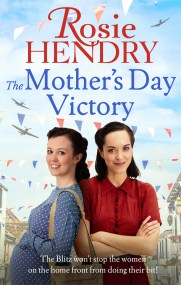

Read an extract from The Mother’s Day Victory by Rosie Hendry

Chapter 1

Oxfordshire, March 1940

‘I’m so sorry to have to tell you this, Anna.’ Mr Jeffries rubbed the bridge of his nose, making his glasses shift up

and down. ‘But as of this Friday I won’t have a job for you. You see, I’m being sent abroad for work . . . so I really have no choice but to send Thomas to boarding school. I’ll be taking him there on Saturday morning.’

Anna stared at him for a few moments, not sure how to respond as the news settled heavily in her stomach. When he’d asked her to come to his study so that he might speak with her, she hadn’t expected this – to be losing her job. And with it, her home.

‘Of course I’ll pay you to the end of the month, and I’ll give you an extra month’s salary in lieu of notice,’ Mr Jeffries added. ‘I really am very sorry about this. Thomas has adored having you as his governess and I know it will be a wrench for him to say goodbye, but I really have no option since I don’t know how long I’ll be away for. At least he’ll be able to stay on at school during the holidays if I’m not back. I’m sure you’ll be able to get another job easily.’ He smiled reassuringly. ‘I will write you an excellent reference, which of course you fully deserve.’

Anna nodded. What could she say? His reasons were sound: he was in an impossible situation – a widower with no family who could take his son in – so sending him to a boarding school was the only choice. She had no idea what Mr Jeffries’ job was exactly, only that it had something to do with the War Office and was important.

‘I understand.’ She dredged up a smile. ‘I will miss Thomas very much; he has been a delight to teach.’

‘You’ve been an excellent teacher. He’s really blossomed under your tutelage, Anna. I only wish you could carry on, but it appears the war has other plans for me, and unfortunately they affect Thomas and yourself too.’ Mr Jeffries sighed. ‘I’ll speak to Thomas about it later.’

He picked up his pen ready to return his attention to the pile of papers on his desk, signalling that their meeting was over.

Leaving his study, Anna retreated into the hall and stood for a moment as she absorbed what had just happened. An urge to weep at the suddenness of losing the job she loved threatened to overwhelm her. She’d been very happy here, the happiest she’d been since she came to England, and now it was ending.

What would happen to her? Where would she go?

Anna sniffed back her tears, telling herself there was no point in crying because it wouldn’t change anything. She had no choice but to accept what was happening and carry on with her job while she still had one.

Turning to go upstairs to the schoolroom where she’d left Thomas working on a story, she caught sight of her reflection in the large mirror hanging on the wall and halted. Her brown eyes stared back at her, stunned and sad. Thomas mustn’t see her like this, she didn’t want him upset, so she pasted a smile on her face, smoothed her shoulder- length bobbed brown hair and firmly reminded herself that nothing in life lasted for ever.

At least she was safe here in England, unlike at home. Far worse things were happening to Jewish people like her under the scourge of Nazi rule back in Germany. Compared to that, losing her job was a minor problem. She’d find another, and a place to live; she would survive and carry on.

Her wages would buy her some much- needed time and she could write to her friend, Julia, who might have heard of suitable jobs she could apply for. She’d met Julia – who was a Quaker – soon after she’d arrived in England. They were helping refugees who’d fled their homes before the start of the war, and the two of them had become friends and kept in touch ever since.

She would be fine, this was just another bump in the road; something to tell her father about when they met again, Anna thought. She had four days left with Thomas and she was determined to make the most of them. They at least had to finish the book they were reading together.

Taking a deep breath, she lifted her chin and headed for the schoolroom that she’d set up when she’d first come to work here last autumn. Her pupil was waiting for her and she had a job to do. For now.

As the train began to slow on its approach into Euston station, Anna stared out of the carriage window at the barrage balloons floating over London like great silver fish. She was trying to distract herself from the image in her mind of poor Thomas’s distraught face when she’d left this morning. He’d been so stoic, seemingly accepting his fate, but when she’d bent down to hug him goodbye his face had crumpled and he’d sobbed in her arms. It had taken all her strength not to break down as well, but that wouldn’t have helped matters. Instead, she’d kissed his cheek and promised to write often, then picked up her suitcases and left without looking back. It was only when she’d reached the end of the road that she’d finally let her tears fall. It was all right to cry, to acknowledge her feelings, she’d reasoned, but vitally important that she carry on and keep going, moving on to whatever came next.

Arriving at the station, Anna gathered up her cases and followed the stream of passengers along the platform, many of them dressed in uniform.

‘Anna!’ Julia’s voice rang loud and clear across the station concourse as the older woman hurried across to meet her, arms flung out for a hug.

Standing back to look at Anna, hands still resting on her arms after squeezing her tightly, Julia gave her a searching look, her eyes taking in every detail. ‘You look well, dear, if a little sad, but that’s to be expected after leaving a post you enjoyed so much. Come on, let’s go

and get some tea.’

‘It is good to see you again,’ Anna said as Julia took one of her suitcases and led her out of the station. On the street, the hustle and bustle of London hit her, the noise and busyness a shock after she’d become so used to the quiet of a small English town.

Looking around, she noticed that signs of a country at war were everywhere, from the strips of tape across windows to the sandbagged buildings and the white- painted edges of the pavements.

‘I’ve had an idea of a job that might suit you,’ Julia said, once they were settled at a table in a small café, a pot of tea between them and a small currant bun each. ‘It’s not something that you’ve done much of before, if at all, but the person you’d be working for is a good friend of mine,

and would be both good to live with and work for.’ She paused while she poured them both a cup of tea. ‘There’s no guarantee, of course, and I didn’t want to write to her and enquire about the job without asking if you’d be interested.’

Anna was intrigued. ‘What would I be doing?’

Julia’s eyes met hers. ‘Gardening.’

‘Gardening!’ Anna hadn’t expected that. Julia was quite right – it wasn’t something she had experience of, having lived in an apartment in Berlin with her father. They hadn’t had a garden, so growing things hadn’t been part of her life, although she’d always enjoyed walking in the city’s parks and gardens when that was still allowed.

‘Growing vegetables and fruit, to be more precise. Not the tending- roses sort of gardening. My friend, Thea, moved back to live in her home village in Norfolk last year, and she’s started to grow fruit and veg, both to eat and to sell to earn money, but with her nephew going off to train for the Friends Ambulance Unit, she’ll be losing her help,’ Julia explained. ‘I know it’s not what you’re used to, but I honestly think it would be good for you. Thea’s a lovely person who’ll welcome you with open arms and make you part of her extended family in no time!’ Her eyes

met Anna’s. ‘Of course, it’s up to you. If you think that gardening is something you really don’t want to do then we’ll find something else. Though I’m afraid it might be domestic work rather than teaching.’

The thought of going back to domestic work and being a servant sent an uncomfortable shiver through Anna. She’d already experienced that and wasn’t keen to repeat it.

When she’d first come to England in early 1939, it had been on a domestic permit, having found a job working as a servant for an old couple in Richmond, but the experience had been far worse than she’d ever expected. She’d been made to do the work of two servants and a cook, and if she struggled to get things done on time their refrain was always, If it’s too much for you, we could always send you back to Hitler.

Thankfully, Julia had come to the rescue and found her the job teaching Thomas, which was far more suited to her skills and was what she loved doing. She’d been a secondary school languages teacher back in Germany, before the Nazis’ regulations against Jewish people had stripped her of her job too. Gardening might not be something she was used to, but it had to be better than working as a domestic servant, and if it was for someone Julia considered a good person, then it was worth a try.

‘All right, I will try it if your friend is willing, but you must tell her that I do not have any gardening experience. I will need to be shown what to do, but I am a quick learner and will work hard.’

‘I’m sure you’ll be fine with Thea. I’d go and help her myself if I didn’t have other work lined up. I’ll be leaving London soon to work in a Quaker evacuation hostel for the elderly.’ Julia took a sip of tea. ‘So, I’ll write to her tonight and we’ll see what she says. Let’s enjoy our tea and buns and then I’ll take you back to my house and get you settled in.’

Anna smiled at her friend. ‘Thank you. I really appreciate your help.’

‘You know I’m glad to do it. I only wish that it hadn’t been necessary for you and so many others to flee your homeland.’ Julia picked up her teacup and took a sip. ‘It’s more important than ever to help each other.’ She paused for a moment, before gently asking, ‘Have you heard any

news from your father?’

Anna shook her head. ‘Nothing, not since he was arrested by the Nazis in October. His friend, Uncle Ludo, wrote and told me what had happened. He had to send it through a friend in Holland . . . I have not heard anything since.’ Her eyes filled with tears.

Julia reached across and patted her hand. ‘Don’t give up hope, my dear.’

Anna nodded and did her best to smile. She was becoming quite the expert in hoping these days. For now, it was all she could do. The fate of her father was out of her hands and with those who would wish him harm.

THE BRAND NEW SAGA SERIES BY ROSIE HENDRY - meet the Women on the Home Front . . .

Can the Women on the Home Front protect their community in times of war?

Norfolk, 1940. As war rages on, sisters Prue and Thea, along with the wider community of Great Plumstead, are doing all they can to help the war effort, from running the mobile canteen for the Women's Voluntary Service to organising clothing drives and collecting salvage.

When, Anna, a young German girl who fled her country, seeks refuge at the local hall, Thea opens up her home, Rookery House, and invites Anna into their growing family. But while many in the village welcome Anna with open arms, others are suspicious of the new arrival . . .

As the war intensifies and panic sweeps the country, Anna is taken by the government who fear she's a spy. The women of Great Plumstead are already fighting their own battles on the Home Front, but will they come together in Anna's time of need to keep the newest member of their community safe from war?

The Mother's Day Victory is the perfect wartime family saga and the second novel in Rosie Hendry's much-loved series, filled with heart-warming friendships, nostalgic community spirit and a courageous make-do-and-mend attitude. Perfect for fans of Nadine Dorries, Donna Douglas and Elaine Everest.

Readers LOVE The Women on the Home Front series:

'I highly recommend this book and give it a well-deserved five stars'

'It's books like this that remind me why I love reading . . . I can't wait to read more from Rosie Hendry'

'Fabulous - can't wait to read the next book'

'Beautifully written . . . Thank you to Rosie Hendry for writing this five-star book'

'A fantastic book - highly recommended'