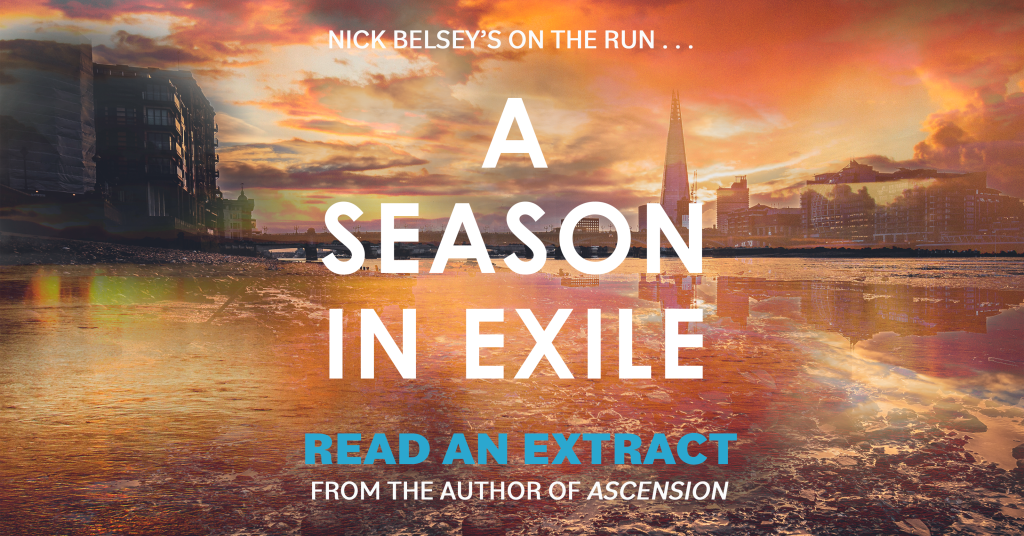

Read an Extract: A Season in Exile by Oliver Harris

Nick Belsey’s on the run.

Touching down in Mexico City, he doesn’t have much in the way of funds, but he has a new continent and surely that’s enough to start afresh. But it’s not as easy as that. An idyllic interlude in a coastal village is interrupted when men turn up who seem to know exactly who he is. And they have some very urgent questions.

DI Kirsty Craik had also hoped she’d left Nick Belsey behind her, in the wilder days of her career. When a five am call instructs her to track him down or she’ll be dead by Christmas, it seems he’s walked back into her life with characteristic commotion. Craik is forced to break the rules once more to find out what her former lover is up to.

She needs to save herself, and, just maybe, to save Belsey too.

A Season in Exile is out in hardback 7 July 2022.

* * * * *

ONE

No one stopped him as he disembarked. He looked for police waiting on the runway but it was empty. Benito Juarez airport sprawled beneath a petrochemical sunset, and Belsey paused at the top of the mobile stairs to fill his lungs. The stewardess grinned as if she was in on the joke.

‘Buenos noches, señor. Bienvenido a Mexico.’

Everyone went to collect their luggage. Belsey had no luggage, which made him feel curiously purposeful, strolling through the corridors alone, empty- handed. A bored- looking immigration official glanced at his passport and nodded him through. So he was first out into the glare of the arrivals hall, greeted like a celebrity by the taxi scammers and luggage handlers. Belsey realised he was smiling at them, amused that they took his existence seriously, the idea he had money and somewhere to go: an Englishman arriving in Mexico City on a Saturday night with nothing but the suit on his back. He was smiling because his life as he knew it was over and he was in Mexico and it felt beautiful.

Shutters started coming down on the airport’s facilities. He checked the signs fast: autobús, cambio de moneda, polícia, cerveza. He emptied his pockets onto a ledge by a closed café and tried to figure out what resources he had. Twenty- six pounds in sterling and several cards of dubious credit. A cleaner mopped by his feet. An old man came up to him and opened a carrier bag, as if furtively revealing his shopping. It was filled with cartons of duty- free Marlboro. Belsey gave him a tenner and took a carton, put it under his arm and walked on.

Sixteen pounds, three debit cards, four maxed- out credit cards, two hundred Marlboro. But a few things in his favour: the weekend, time difference, the fact that most businesses processed transactions in batches at the end of the day. All this created a fissure of opportunity between expenditure and consequence that might be wide enough for him to slip through. At least two of the cards would let him go over the limit at the risk of heavy fines attached to billing addresses he no longer remembered. The concept of financial penalties felt weak. He tried a cash withdrawal but that didn’t work. Nor did the bureau de change, but he managed to buy a bottle of water from the 7- 11 using an old Amex, which meant the card was alive. He had credit.

He skipped the international car- hire companies and went to the last on the row: Optima Auto Rentas. A sleepy kid roused himself and turned his computer on. Belsey asked for the most expensive car they had and was offered a Dodge Charger for forty dollars a day. He requested use of it for six days, gave his address in Mexico City as the Hilton.

‘Hilton Reforma?’

‘That’s the one.’

Belsey watched with a mounting sensation of weightlessness as the boy typed it in, took a carbon paper copy of the Amex, had Belsey sign a couple of forms, then found keys in a drawer beneath his desk. He led Belsey down to the car park, and ten minutes later Belsey was on the road.

This was the real test. The slip road fed into a crowded dual carriageway. Eight lanes of traffic poured into town with an attitude somewhere between a race and a carnival procession: high end SUVs and cars held together with string, all weaving and nudging, everyone driving like they were on the run a thousand miles from home, which was an edgy kind of incognito. Indicators weren’t a thing. Sometimes they came on but whatever it meant it wasn’t what he’d previously understood. Neither were lanes. If you opened up a gap between you and the car in front someone would cut in so you had to become one with the flow. People threw the hazard lights on before braking. Traffic cops stood on every corner, watching this communal death- wish without judgement. Belsey’s adrenalin pumped, everything very vivid now, a plan becoming real even if he wasn’t sure what it was.

A carpet of concrete slum homes stretched up the hills either side towards a night sky dulled by light pollution. The silhouette of a volcano came in and out of view. Cars heading east had a coating of ash. He kept an eye on road signs. Mexico City didn’t exist. On the signs it was Distrito Federale. ‘Federales’ was the name painted in white letters on the paramilitary trucks tearing through the traffic: open- backed jeeps with men in black combat fatigues stroking their assault rifles. They were something different from the Policía Municipal, who cruised in convoys of seven or eight vehicles with lights and sirens on. Belsey kept alert, but after a while he realised there was no emergency: that was just how they moved. Or it was all an emergency. He stopped checking the mirrors every time they flashed.

The city grew around him, street- level chaos closing in: little cafés next to glass blocks with armed guards; heavy churches sinking crooked into the ground. No one was ever going to find him here. He reached the centre of town on a big, buzzing avenue called Insurgentes. Everything was fine. He let himself breathe.

What did he look like? Just some caballero heading home from work. No one even glanced at him. So this was exile, he thought, like a lucid dream. He could move through it. He could breathe in it, and it felt like being able to breathe underwater. What was the catch? Just keep going, stay out of trouble. He needed to switch vehicles, get some cash, that was all. The plates on the car were still tagged to his name, and while he couldn’t imagine a transatlantic manhunt leaping into effect any time soon, it cramped his sense of freedom. There was no such thing as half escaping.

He kept heading south into a lot of cheap construction with wiring feeding into homes from pylons. Isolated pools of yellow streetlight caught curtained doorways. The stop lights in this part of town flashed continuous red as if they had a dark sense of humour.

Belsey stopped when he saw a cantina called Salon Casino. Maybe he could win some money, he thought. What games would they have? He parked right outside so he could keep an eye on the Dodge through the doorway.

Salon Casino had no casino, it turned out, but sold a beer called Techate at ten pesos a bottle. The place was small, low- lit, with football memorabilia on the walls. Men stopped drinking to watch Belsey enter. The barman had a deep crease up one side of his bald scalp. Belsey offered a box of Marlboro in return for a couple of drinks. He tried to rustle up some of the Spanish he’d been learning.

‘Uno box, dos cervezas. Sí?’

The barman reflected, then tossed two beer mats in front of Belsey and set down the bottles, beaded with condensation. He placed the pack of cigarettes in his top pocket. Belsey lifted a bottle in thanks.

The man seated on a stool beside him laughed. He wore overalls, had greasy hair and high Aztec cheekbones. He’d been glancing at the Dodge outside with quiet curiosity. Now he raised his own beer in a respectful ola.

‘Cheers. I just got here,’ Belsey said.

‘Doctores?’

It took Belsey a while to understand what he was saying. It turned out he was in an area called Doctores and that wasn’t a good idea. Not for tourists anyway.

‘I’m not really a tourist,’ Belsey explained. He offered the man his second drink. The man accepted. He spoke good English. He said he’d spent several years in California.

‘Would you like to buy some cigarettes?’ Belsey asked.

‘Why not?’

The man paid for the cigarettes out of a roll of grubby, untaxed notes.

‘You’re a mechanic?’ Belsey asked.

‘Sure.’

‘Perhaps you can help. I’ve got a car outside that I’d like to trade. Drives beautifully – a Dodge Charger. Not many miles on the clock. Just too big for my needs, and I could do with some money fast.’

‘It’s a nice car.’

‘Any idea where I should go if I wanted to sell it quickly? For cash?’

‘How long have you had it?’

‘About an hour.’

‘How much do you want?’

‘Say a hundred dollars and some alternative wheels. Nothing fancy.’

The man laughed, sipped his beer. When the beer was gone, he surprised Belsey by getting up, glancing out through the doorway again. ‘Come,’ he said.

They went out. The mechanic asked to see inside the Dodge. Belsey gave him the keys. He stuck his head in, checked the mileage, the upholstery, breathed deeply. He came out, circled the vehicle, crouched and dug a thumbnail into the tyre tread. Then he straightened and they crossed the road to a breakers’ yard with big metal gates. The road sign next to it said ‘Dr Lavista’. The man unlocked the gates and dragged them over the stone pavement, firing sparks. He went inside, hit the lights. A neon- lit cave appeared, filled with jacked- up cars, the sides piled high with rear- view mirrors, windscreens, radios and steering wheels. There were more cars at the back, in a high- walled yard, a lot with US plates, a lot with identifying tags burned off.

‘Any of these drive?’ Belsey asked.

‘Sure. You used that car in a crime?’

‘No. I’ve only been in the country a couple of hours. I just need some cash.’

‘It’s a hire car.’

‘It’s a hire car, sure.’

The mechanic’s eyes cut to the front. He sucked air through his teeth, then led Belsey to a 1970s Maserati, chocolate brown apart from the front passenger door, which was a black replacement. If you squinted, it had a profile like an old Jag.

‘This one drives. I give you this, hundred dollars, we shake hands.’

‘Two hundred.’

‘One hundred.’

‘Okay.’

The man gave Belsey some more sticky notes and the keys for the Maserati. He seemed happy enough. ‘Make sure you pump the brakes. Give it plenty of time. And the steering will need a bit of muscle.’ He mimed steering vigorously. He looked a little concerned.

‘I’ll try my best.’

‘Any more I can do?’

‘Which way’s the sea?’ Belsey asked.

The man brought up a map on his phone.

‘There’s a lot of sea. Where do you want to go exactly?’

Belsey touched his finger to the screen and moved the territory around until he saw what he wanted. ‘Acapulco,’ he said.

TWO

He was out of the city by daybreak and felt safe enough to park for a few hours behind a service station and sleep. When the heat woke him, he got out of the car and stretched, and felt like he was in exactly the right place for the first time. He bought three litres of water, sunglasses and a fold- out road map. It looked like Highway 95 would take him to the coast. He could make Acapulco in a few hours if he floored it, a couple of days if he went more scenic.

The car drove for now. The radio worked. He played rock music as he accelerated out of a national park, keeping the volcano to his left, which meant he was going south. Onto Highway 95, through villages with stone houses, into the state of Guerrero. Get to the sea, he thought. There would be space to think there. Then, once he’d decompressed, he could work his way back into something. But he needed to fully escape first.

He met Esmerelda at a petrol station where Highway 95 met a toll road heading north. She was standing in the shade of the canopy, watching Belsey as he filled the tank and paid. When he walked back to the car he gave her a nod in greeting and she walked over.

‘Buenos días,’ Belsey said.

‘Americano?’

‘Inglés. Need a lift?’

‘Where are you going?’

‘Acapulco.’

She smiled. ‘Me too.’

She had long black hair, sandals and shorts, a canvas overnight bag with tassels. She put the seat back so she could stretch out. He wondered what her eyes were like behind the shades.

‘What’s your name?’ she asked, when they were on the road.

‘John.’

‘Johnny B. Goode.’

‘That’s the one.’

She said she was Esmerelda, and had been on her way to visit her sick mother when her previous ride broke down. She didn’t try to make it convincing. Belsey thought back to when he first saw her and realised she was on the watch for something. Their click was the encounter of a police officer and a criminal. He didn’t give a fuck. He had eighty dollars, a Maserati and quite possibly an international arrest warrant on him. She could only enhance the situation.

‘Are you on holiday?’ she asked. ‘On your own?’

‘Holiday of sorts. I’m taking a break from things. Needed some space.’

‘What is your job?’

‘I’m between jobs. I’m an actor. I do bar work. Whatever’s

going.’

‘Are you famous?’

‘Not yet. Getting close.’

He gave her a pack of Marlboro and she lit a cigarette for him. They drove, chatting about life, its twists and turns, through Iguala, with its tamarind trees shading the road, then into the mountains, rising above industrial grime and more ramshackle buildings. They passed Zumpango del Río, where she said there were abandoned silver mines but he didn’t see any. The hillsides were lush with greenery now. Belsey stopped and they got lunch from a roadside restaurant with a terrace overlooking the valley, which used up a lot of his currency. But it was nice to have company. His passenger took her shades off and her eyes were chestnut brown but deep with a knowledge of things that could happen and were to be avoided. He checked her bag when she went to take a picture of the view and found six cheque books in different names, none of them Esmerelda.

They were still on the road when it got dark.

‘Let’s get dinner,’ Belsey suggested. ‘Then we can rest and start again in the morning. Can you do that?’

She took a second to consider this. ‘Sure. It’s a good idea.’

So they stopped at Chilpancingo, a decent- sized town which promised nightlife. Belsey found a motel. He offered to pay for two rooms. Esmerelda said one would be fine, which made the dinner a lot more relaxed. They went on to a club decorated in the style of old taverns with a mechanical bull in the centre of the dancefloor.

‘I’ve never seen one of these in a club before,’ Belsey said. ‘It’s a great idea.’

The tequila was cheap. Esmerelda had pharmaceuticals: sky blue rocks of crystal meth and something like codeine in white pills. They smoked the meth from a glass pipe and dropped a couple of the tranquillisers and walked around Chilpancingo, checking out other bars, dark ones where they had to lean close to see each other’s eyes.

‘In the car park, where I picked you up,’ Belsey said, ‘you were looking for something.’

‘Was I? Maybe I was looking for you.’ She smiled.

‘You looked like you were going to steal a car.’

‘Me? Steal a car?’

Crossing the forecourt back to their motel room Belsey felt the earth rising up towards him, lifting his feet. Mexico was just another place, but a new one, and the thousands of miles between him and the UK swaddled him, just like the night air did. And he was heading to a twenty- dollar motel room with a woman whose real name he didn’t know, less than forty- eight hours after arriving in the country. What greater sign was there that all was well in the universe?

They hit the road early the next day, stopping for breakfast and then a couple of remedial cocktails. He was starting to hurt – little stabs of pain in specific organs. But he put it down to a hangover. Esmerelda introduced him to something she called a Michelada, which was like a Bloody Mary with beer instead of vodka, and he introduced her to the Easy Flip with stout, bourbon and black coffee. The caffeine was valuable. By the time they reached El Ocotito, a town with two bars, a post office and an industrial park, they were low on money. She told him to stop outside the post office. Belsey watched her go in, and after five minutes she left again, climbed back into the Maserati and Belsey drove fast.

‘I’m good at gambling,’ he said. ‘Poker, slots, whatever. If there’s a casino I reckon I can double what we’ve got.’

There was no casino. They passed villages of pink stone, then larger towns with small demonstrations going on in their central squares. Against corruption, Esmerelda explained. It seemed like something was kicking off in Guerrero state. They did shots of white rum at roadside bars and smoked the rest of the Marlboros. Fifty miles north- east of Acapulco they hit a checkpoint.

Men in ambiguous uniforms with unambiguous weaponry stood across the road, manning a roadblock constructed of concrete sections from the side of the highway. Esmerelda told Belsey to put away any valuables, to approach slowly and not make any sudden movements. She’d do the talking.

‘Police got issues?’

‘It’s not the police.’

She was right. The cars were faded and they wore trainers.

‘Who are they?’

‘People. Maybe soldiers.’

When it got to Belsey’s turn the men stuck their heads in, walked around the car and made Belsey get out and open the boot. He realised he hadn’t looked in the boot but all it contained was a flat spare tyre and someone’s snakeskin boots. Esmerelda smiled sweetly, talked about visiting her family and her cousin’s first communion, and they got through, but it felt lucky. After that they stuck to toll roads. Most of the time it was mesa either side, rugged with low peaks. When they passed a church ringing its bells Esmerelda put her fingers in her ears. She said she couldn’t stand the sound of church

bells.

‘Why?’

‘Have you heard of the earthquake in Manzanillo?’

‘No.’

She told him about her childhood, further up the coast in a small town called Manzanillo. There had been a terrible earthquake when she was eight, she said. Took most of her family. She held back tears as she described waking up in the middle of the night and all the church bells were ringing on their own. She never forgot the sound. ‘My life would have been different if it hadn’t been for that earthquake. I would have gone to college.’ She said she’d never been in a nice hotel, never really been on holiday.

Belsey checked the map and decided on a diversion. Hotel San Luis Lindavista was by an archaeological site on the Río Papagayo. It was only a couple of kilometres out of their way. ‘One night,’ he said. ‘Let’s blow the rest of my money.’

She smiled, and slid a crooked finger behind her sunglasses to wipe each eye in turn. ‘Let’s do it.’

The hotel greeted them warmly. Belsey did the talking this time, and they signed in as Mr and Mrs Cash. It had a pool and a restaurant. They wore the bathrobes, opened the minibar, ate the chocolate and Pringles and drank the miniature bottles of wine.

Belsey stood in the light of the bathroom mirror wondering if his skin was yellow or if it was the light. He had a dawning sense that he wasn’t well, in a profound way; that he hadn’t been for some time. The drugs helped temporarily, but he was putting something off. The medication he needed wasn’t the kind he was getting. They finished the wine, smoked the rest of the meth. Belsey considered telling her he’d started urinating blood. It felt like a big confession when they’d known each other only a day or so.

When he woke up she was gone. He was in a very bad way then. The sheets were bloody, and there was a sharp reek of bile. He thought at first she’d left because he’d vomited blood over the bed, which would have been understandable. His belongings were strewn everywhere, wallet gone, along with paperwork and car keys.

That stung, but he could look back and see it as the conclusion of a far more elaborate hustle, one he’d wandered into before he could remember. Life was a con. It was worth every penny. He laughed and a white pain cut through him. He sat down on the bed and held his head in his hands.

After a few minutes Belsey had the strength to get to his feet and mop up the last of the drugs from the bureau. This gave him the presence of mind to take the clothes iron out of its little linen bag and empty the rest of the minibar into the bag. He left the hotel, nodding at the receptionist, saw his car missing, made it to the road where he hitched a lift.

The first group that picked him up took offence when they realised the state of him. It was a crew of four men, drunk, driving a van. They tried to rob him but couldn’t find anything to rob, so they kicked him out of the vehicle, then got out and started kicking him in the head. When they were done, Belsey remained curled up for a while, letting his new injuries throb.

Next lift was a serious guy in a brown suit, who seemed to understand something about Belsey’s situation. He gestured solemnly at the passenger seat without taking his eyes off the windscreen.

The man drove steadily. His car was falling apart. The exhaust system rattled beneath them, and both wing mirrors had departed. He had a handsome, unevenly shaved face, and elegant fingers, which he drummed on the wheel as if to music Belsey couldn’t hear. He asked Belsey for help reading signs and Belsey realised he was partially blind. They shared drinks. Belsey gave the man some of his minibar haul. The driver had mezcal in a litre Coke bottle, crazy moonshine that tasted of burning tyres. Belsey felt momentarily fortified and lucky. He imagined the two of them helping each other as they made a slow but important journey across the decimated surface of the earth. The man said he was going to see his son, who worked in a hotel and whom he hadn’t visited in twelve years. He hadn’t driven for a while also, he said. Belsey persuaded the man to let him drive and they swapped places. The man talked more from the passenger side. He had been driving many days, he said. He was a Jehovah’s Witness. He fell into a stupor. Belsey put the seatbelt on him to stop him falling face first into the dashboard. At some point Belsey must have blacked out too because when he next opened his eyes they were parked at the side of the road, the man asleep beside him. It was night. Belsey could smell the sea.

He took the remaining pesos from his pockets and put them into the man’s jacket along with a couple of miniature Smirnoffs. Then he stumbled out of the car and walked the remaining distance to the coast, each step a victory against whatever was going on inside him.

After a couple of hours he got to a beach with small boats lined up on the sand. Houses made of corrugated metal and raw concrete faced the sea. Waves glittered in moonlight. It wasn’t Acapulco but it would do. He stood right by the water so he couldn’t see anything else and had a sense of having arrived at the far shore of his life. His peripheral vision was gone. The sea was in his shoes. He let himself sink down until he was kneeling in the amniotic warmth of the Pacific, salt water lapping his thighs, and everything within him said good night, game over, and he understood now why he had been coming here, what he was here to do.

PRE-ORDER NOW: