Read an extract from Days of Wonder by Keith Stuart

Tom

There is such a thing as magic. That is what I always believed. I don’t mean pulling rabbits out of hats or sawing people in half (and then putting them back together: otherwise it’s not magic, it’s technically murder). I don’t really mean fairy- tale magic, either, with its princesses and witches and frogs that turn into handsome guys – although fairy tales will certainly play a part in our story. I just mean the idea that incredible things are possible, and that they can be conjured into existence through will, effort and love. That’s how it started. That’s how we got through everything in the way we did.

I suppose I really ought to begin with Hannah’s diagnosis, but no, we’re not going there, not yet. This is a story about magic, and therefore I will start somewhere magical. Or kind of magical. Oh look, it’ll make sense, trust me. Let’s begin two weeks after the diagnosis, on Hannah’s fifth birthday – because this is what life is like sometimes: you’re planning for a big day and then suddenly – pow! – have some shocking news about your daughter, no, go on, I insist. Of course, I didn’t explain things fully to Hannah, how could I? But she was already wise, wiser than me – wise enough to look into my eyes and understand the essence of what the doctors had told me, and what was coming. We stood at the bus stop outside the hospital, the cold sun glinting off the scratched Plexiglas shelter. I tried hard to swallow, but it felt like I had a bowling ball in my throat. She looked up at me.

‘It’s okay,’ she said. ‘It’s okay.’

And she put out her tiny fist for me to bump. I bumped it.

Anyway.

Anyway.

Where was I?

So yes, I thought, I have to do something special for her birthday – something to take us out of this place. I asked her what she wanted, and she shrugged and said, ‘I just want to play Lego with my friend Jay.’ That’s easy enough, I thought.

‘And fairies,’ she added. ‘Can I have real fairies?’

She had this book she absolutely loved – a fairy tale collection that had been handed down through my mum’s family. It was incredibly ancient, so had none of the neurotic delicacy of a modern translation: kids died in the forest, dwarfs were eaten by witches, wolves butchered woodcutters – just horrible stuff. Hannah adored it. But she especially loved the idea of fairies – not the supermarket fancy- dress fairies with their pink sparkly wings and crystal wands, but the old- school fairies; the mischief-makers, cavorting in the woods and trapping humans in magical glades. Whenever we got to the end of a story, she’d always sigh and say, ‘But fairies aren’t real, are they?’ and I’d tell her they definitely were, but that only special people got to see them. It was just a joke, a little routine to end the day. But on that night, the night of her fifth birthday, she asked as usual, only this time I said to her, ‘Look out of the window later and you may be lucky.’ She laughed at me dismissively, and buried her head in the duvet until I got up to go. But I knew she was curious, because she was always curious.

So I kissed her on top of her head, her curly hair bedraggled and knotty because neither of us were any good at combing it; then I walked out of the room, closing the door behind me – except I left a gap, just enough to peek through. And sure enough, when she thought I was gone, she pulled back the duvet and crept towards the window . . .

I should explain at this point that I was a theatre manager, and before that an actor. When I was eight my parents took me to see Dick Whittington one Christmas and that was it, I was hooked. I begged them to take me back the next night, and the next. As a teenager, my friends were following Bowie, Pink Floyd and the Clash, while I was obsessed with the RSC, the Royal Court and the Old Vic. The magic I always believed in most was the magic of the stage, the miracles that take place when you put performers in front of an audience. You should bear this in mind for what comes next.

Outside Hannah’s room, the night was almost completely black, the stars obscured behind a layer of distant cloud. Our house backs onto a field and during the day we’d sometimes see horse riders pass by, following the bridleway up to the woods. But at night there was nothing but darkness and then the distant twinkling lights from the next town miles away.

I could see that Hannah was now on tiptoes at the window, her small body silhouetted against the darkness outside. Suddenly, her head flicked to the right. From behind the tall hedge at the rear of our neighbour’s garden there was a curious glow, orange and warm, like a bonfire – except there was no crackling, just the sound of very gentle music, almost lost in the buffeting wind. Then, indistinct at first but gradually louder, there were voices too. They were singing. I heard Hannah take a sharp intake of breath, and then she rubbed furiously at her eyes with the sleeve of her pyjamas, before staring out again. She didn’t move away, she didn’t shrink from the window – she stayed still, as though entranced, as though connected to whatever was happening outside. Then as the music got louder, she somehow stirred from her reverie.

‘Daddy!’ she shouted. But there was no fear in her voice; it was not even shock or surprise. It was delight.

‘Daddy,’ she said again. ‘I can see them, I can see them!’

‘See what?’ I said. And I was bounding into the bedroom, pretending that I had no idea what was going on. She grabbed my hand and dragged me to the window.

‘The fairies,’ she said. ‘There are fairies here!’

And sure enough, dancing along the bridle path at the end of the garden, waving and smiling as they passed, was a line of beautiful figures in luminous white dresses and giant fluttering wings. Some held lanterns suspended from long staffs, the candlelight flickering as they moved; others were wrapped in shawls of flashing fairy lights. Hannah watched, at first transfixed, then banging on the window, waving delightedly. When one figure stopped, leant on the garden gate and blew a kiss up towards the window, she gasped. It was the first time in a week I’d seen her forget herself and everything else. If only for an instant, it wiped away the darkness of the preceding days. The figures danced and sang, the light from the lanterns forming a halo around them. Gradually, as the caravan of fairies passed, the music faded and the glow dispersed. The darkness returned, but not as deep or as black as it had once seemed. Something of the fairies had been left behind for ever.

I’ll let you into a little secret. Technically, they weren’t fairies. If you listened carefully you would recognise that the music was not some enchanting lullaby or mystical ballad – it was ‘When Two Become One’ by the Spice Girls, playing on a ghetto blaster. The thing is, when you manage a theatre, one of the perks of the job is twenty- four- hour access to enthusiastic amateur actors, who respond positively to the request, ‘Will you come and dance past our house on Sunday night dressed in glowing leotards?’ We also had a reasonably stocked props department so getting hold of Victorian lanterns at short notice wasn’t as much of a problem for us as it would have been for someone relying on Homebase.

Anyway, I’d found this silly way to lighten the darkness, and it had worked. Eventually, Hannah bolted from the window and made for the stairs, determined to see the show up close. But by the time she got to the back door, the fairies were long gone (as we had arranged), scarpering into the alley a few houses down. I still don’t know if she believed they were real or knew it was a show, but when I caught her up, she was standing in the open doorway, the breeze blowing her hair around her shoulders. She glanced up at me, then grabbed my hand.

‘Again,’ she said. ‘Again.’

I suppose it was clear from that point that Hannah would be a sucker for escapism, for theatrical wonder – it was in her genes after all. As for me, I knew I had a way, however trivial and momentary, to help her cope with what had happened, and what was to come. I knew make- believe would be important.

So every year I arranged something like this for her birthday. A little play, a little surprise. It became something of a ritual to ward off the reality of the health tests and assessments that closed in every autumn.

The years passed, faster than I could ever have imagined, and when she was thirteen she decided she just wanted to spend her birthday with her friends. A walk into town, pizza, videos. It was always going to happen. All the make- believe in the world will not stop time.

Three months before her sixteenth birthday, I began to wonder if there was time to put on just one more show for her. It felt important – as though a little part of the future depended on it. I had this persistent feeling that something terrible was coming – we needed to be prepared and this was the only way to do it. I was a big believer in the magic of the theatre, you see. Did I mention that?

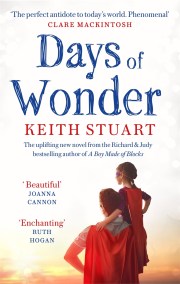

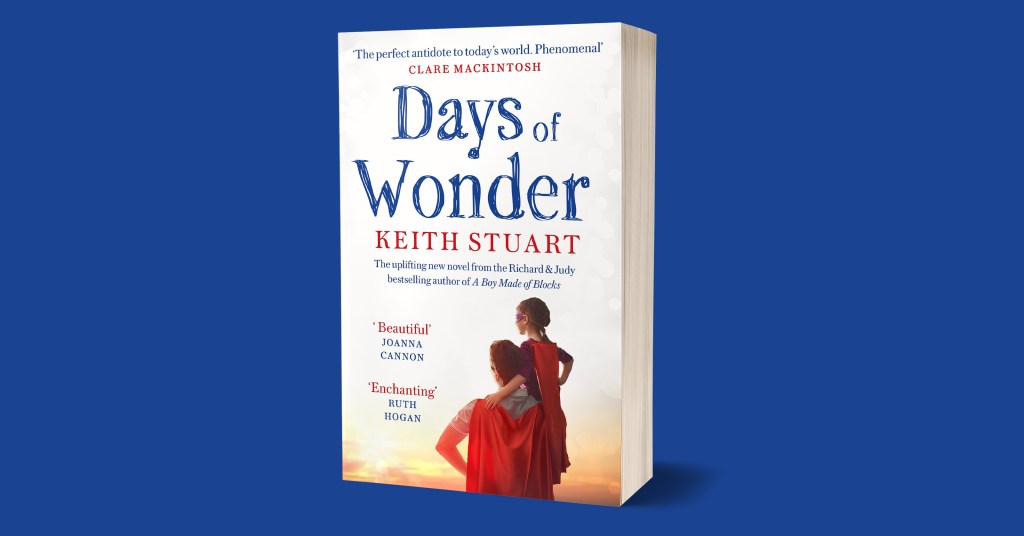

'A story of life, love and hope - the perfect antidote to today's world. Phenomenal'

CLARE MACKINTOSH

The incredible, life-affirming new novel by the author of the Richard & Judy Book Club Bestseller A Boy Made of Blocks for fans of Matt Haig and Jojo Moyes.

Tom, devoted single father to Hannah, is the manager of a tiny local theatre. On each of her birthdays, its colourful cast of part-time actors have staged a fantastical production just for her - a day of wonder. However hard life gets, all Tom wants to do is make every moment magical for her.

Now, as Hannah begins to spread her wings, the theatre comes under threat of closure and the two could lose one another. But maybe, just maybe, one final day of magic might just save them both.

A story about finding joy in everyday life, Days of Wonder is the most beautiful and uplifting novel you'll read all year.

'Days of Wonder is a heartwarming and magical story. A wonderful read' LIBBY PAGE, AUTHOR OF THE LIDO

'So powerful, yet incredibly gentle and poignant. Utterly and completely beautiful' JOANNA CANNON

'Utterly enchanting . . . a truly beautiful story' RUTH HOGAN

'This is the most emotionally powerful book we've read all year' HEAT

'Tugs at your heart' DAILY MAIL

'Fans of Jojo Moyes' Me Before You will love Days of Wonder. Made me laugh and cry in turn' GOOD HOUSEKEEPING

'A lovely, funny and very moving novel' SUN

'It's a long time since a book made me laugh out loud and cry so much' TRACY REES

'A beautiful read' CLOSER

'The publishing sensation of the year' MAIL ON SUNDAY ON A BOY MADE OF BLOCKS

'An uplifting read, full of humour and heart' SUNDAY MIRROR

READERS LOVE DAYS OF WONDER:

'Beautiful. Powerful. Emotional. Heartwarming. Bold. Touching. Heartbreaking. Wonderful. Outstanding. Brave. A must buy. A must read' BETWEEN THE PAGES BOOK CLUB

'I didn't think Keith's novel A Boy Made of Blocks could be topped, but he's done it' GOODREADS REVIEWER

'This is a truly wonderful story, and I recommend it to anyone with a heart - broken or otherwise' GOODREADS REVIEWER

'I can't stress how amazing this book is. I truly believe that 2018's must-read novel has arrived' WHISPERING STORIES

'Catapulted itself into my top five reads of all time' GOODREADS REVIEWER

'Brilliantly done and backed up with a cast of lovely characters. I adore this book' GOODREADS REVIEWER

'Just wonderful, a delicately finished story full of joy, loyalty, heartache and love' GOODREADS REVIEWER

'Keith Stuart is fast emerging as one of the UK's great emotive writers when it comes to finding the beauty in everyday life' BEN VEAL WRITES

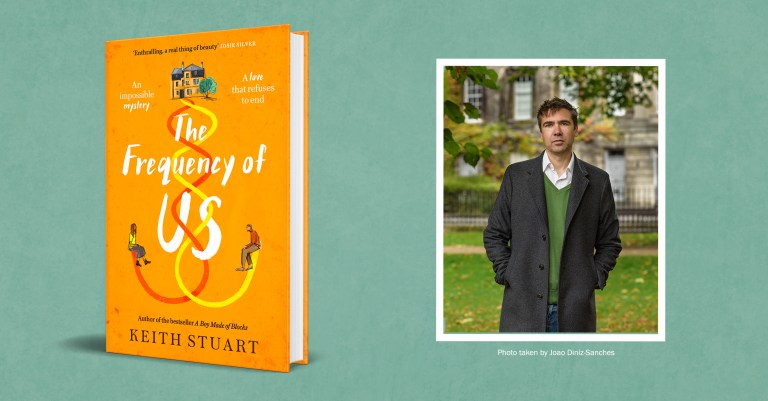

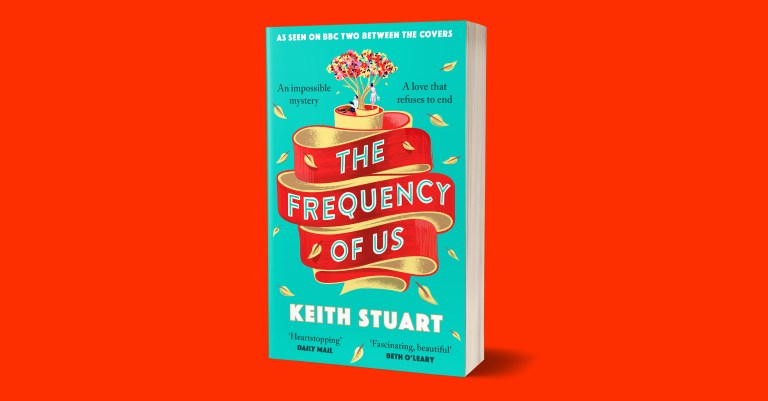

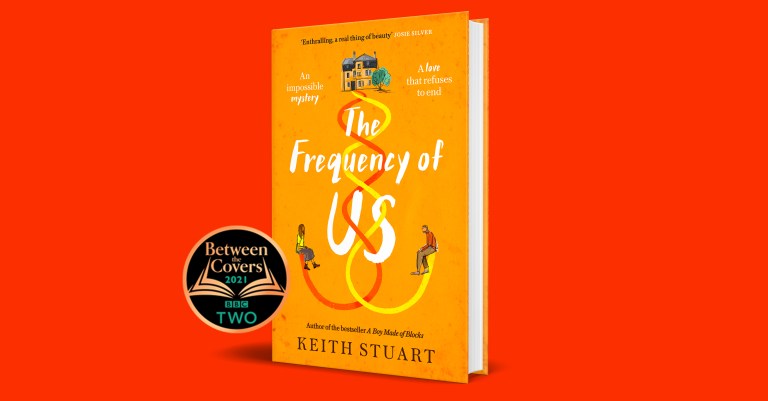

Pre-order Keith’s new novel, The Frequency of Us, now on the link below