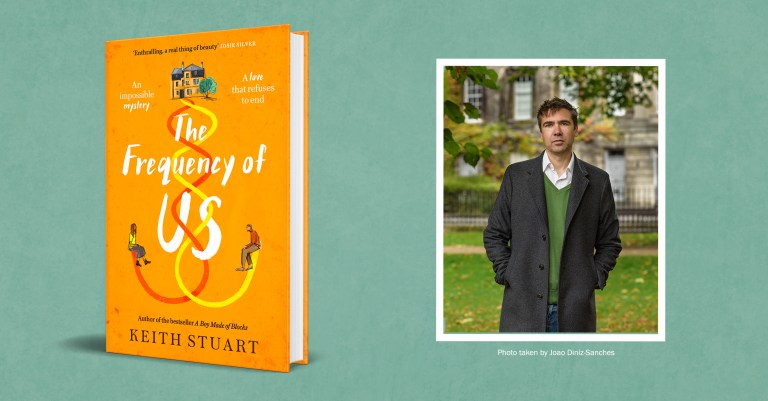

Read an extract from The Frequency of Us by Keith Stuart

Part One

DISAPPEARANCE

26 April 1942

The sirens woke Elsa but not me. I’d crawled into bed only an hour or so before, exhausted, bruised, desperate to blot out the memories of the previous day; the awful things I’d seen. She was shaking me, harder and harder, and even then sleep would not release me. Finally she shouted, ‘Will! Will! Wake up! Will, darling!’

‘What is it?’ I groaned, turning away from her, pulling the blankets up and over my head. She switched on her bedside lamp.

‘Will, we have to go.’

For several seconds, I still couldn’t understand her, desperate to return to the peace of unconsciousness. But then I heard for myself. The ululating wail of the sirens, and beneath them a sound like rolling thunder coming in. The bombers. The bombers were back.

Elsa was up and out of bed, pulling on her thick dressing gown, bumping against furniture in the darkness, a growing frenzy of movement and panic. I sat up, rubbing my eyes, and for a few seconds I entertained the possibility that the planes would pass overhead, as they had every night before last, on their way to Bristol. But just as I was about to reassure Elsa, we heard the high pitched whistling sound of falling bombs, dozens of them – a horrible choir. Then multiple impacts, low and distant. We looked at each other.

‘I’ll need to get dressed,’ I said. ‘I have to report in.’

‘You can’t, you were out all day yesterday. For God’s sake, let someone else go.’

‘It’s my duty.’

As I dressed, Elsa peeled back the black curtain and looked out of the window. From here, we had a panoramic view over the city; it was one of the reasons my parents bought the house. How lovely, my mother often said, to see Bath laid out before us like a picture postcard. Last night, we’d seen a very different prospect, vast areas on fire, like some awful vision of the apocalypse.

‘Will,’ said Elsa. ‘There’s someone in your workshop.’

A cold chill went up my spine. ‘What? Are you sure?’ My shirt still unbuttoned, I joined her at the window and looked out toward the end of the garden. Sure enough, there was light seeping from beneath the workshop door. A shadow moved inside.

‘Looters?’ said Elsa.

‘Surely not. I’ll go and see.’

‘No, Will, we have to get to the cellar!’

There were more long droning whines, seemingly nearer now, and then three massive explosions that shook the whole house. Outside, someone very nearby was screaming. The sound jolted me back to yesterday; the houses on the Lower Bristol Road, all obliterated, like a row of grotesque blackened skeletons. Bodies in the soot.

‘You go,’ I said. ‘I’ll have a quick look, there’s a lot of equipment in there that . . . ’

‘Oh forget your damn contraptions, Will, come with me. Bitte!’

‘I’ll only be a moment, darling. I promise.’

When I opened the back door and looked out beyond the garden, the horror of it all hit me again. The smoke billowing beneath the red glow of the flares; the rumble of falling masonry; a smell in the air like molten tar. From further down the hill the gut- wrenching sound of another explosion, then cries from God knows where. Another wave of bombers was coming in for its turn at the city, untroubled by the pathetic patter of distant anti- aircraft fire. Bath had no defences of its own. No one had expected this. I felt a hand on my elbow. Elsa was behind me in the doorway. I turned and kissed her.

‘Go to the cellar,’ I said.

She looked at me desperately, but started stepping back toward the cellar door, and for a moment I thought of following her. Instead, I scrambled out toward the workshop. My father had built it many years ago; my brother and I helped him, carrying bricks along the garden in a rusty old wheelbarrow. There had once been an orchard down there, he told us. As I got closer to the door, I could hear someone speaking inside; instinctively, I looked around for a weapon, a spade or pitchfork, anything. But then as my senses gathered, I realised with a start that I recognised the voice. I wasn’t sure whether to feel shocked or relieved. I opened the door very slowly. The interior was mostly lost in shadow, but a single lamp illuminated the large work table in the centre of the room, crammed with half- built wirelesses, tools and components. At the rear, a window overlooking the city let in a little more light, revealing the metal shelves lining the walls, loaded with more tools and parts. My father had tinkered with his car in here, but for me it was always wireless sets; there were several models I had bought or scrounged from work, several more I had made myself. And there, sitting at the desk with his back to me, one hand desperately fumbling with the dials on my radio transmitter, was a small boy, dressed in striped pyjamas.

‘David,’ I said. I spoke quietly, calmly, so as not to startle the lad, but I was aware we had to get out. ‘David, what on earth are you doing here?’

Before he could answer there was a series of blasts, not far from us, perhaps along the road toward Camden Crescent. The whole building shook, releasing a shower of dust from the low rafters.

‘David,’ I said again, gritting my teeth to stop myself from yelling.

‘I’m calling Daddy,’ he said. ‘He’ll rescue us.’

‘I’m sure your father is on his way, but we have to get to safety. Does your mother know you’re here? David, she must be frantic.’ I was terrified she would be out looking for him, combing the streets while the bombs fell. Should I take him back to his own home? He lived only a few houses along from us, but it seemed a tremendous gamble.

‘Come with me to our cellar, you’ll be safe with us. I’m sure Elsa will sing to you. Some of the songs she has been teaching you on the piano, perhaps?’

He turned away from the transmitter and toward me.

‘The Grand Old Duke of York”?’ he asked.

‘Yes of course.’

‘But my daddy . . . ’

‘Your daddy will know we are in trouble. He’ll fly in his plane and he’ll shoot the Germans down, I’m sure of it. But for now, we have to go.’

‘But how will he know?’

‘The RAF has lots of technology to let them know what is happening in the war. I’ll tell you all about it inside.

’I wished I’d never taken him out to see the workshop; a few months ago he’d been over for his weekly music lesson, talking about his father and his Spitfire, and I’d told him about how pilots used radios to talk to each other.

‘Come and see,’ I had said. I showed him the transmitter and explained how it worked.

He had asked, ‘Could I talk to Papa on that?’

Since then he’d been a regular companion, helping me to clean the sets, replace valves – I enjoyed his enthusiasm, it reminded me of myself at his age. Through the grimy window I could see flames licking the skyline. Something vast was on fire down there – perhaps the whole city this time, perhaps everything. And then my eyes rose slowly, attracted by an all- too- familiar noise: high up, but caught unmistakably in the bright moonlight, there were three bombers, heading in our direction, stark and black like mythical beasts.

‘Oh Jesus,’ I whispered. Without thinking I leapt forward and grabbed the boy, knocking the chair from under him. He screamed and grasped at the radio microphone, but I had him in my arms as the noise grew louder. This is it, I thought. We either dive under the work table or make a run for the house. I had seconds to choose. The house. David screamed and punched at me as I kicked open the workshop door.

‘Here we go, old boy,’ I said and I bolted out onto the path.

Almost immediately a gust of hot, smoky wind hit me, filling my lungs. The sky was molten, the glow of fire reflecting in the windows of the houses. I stopped for a moment, almost transfixed by the horror of it, but the planes were so close now, I had to be fast. It was a steep climb back up the garden to the house with David in my arms, and after all that had happened yesterday I was worn out, my muscles ached. There was a cacophony around me. The sound of throbbing engines filled my ears like blood. About halfway across the garden, I saw a figure standing in the doorway to the kitchen. It took my eyes a few seconds to adjust, but it was Elsa and she was shouting something. I was about to yell that she should go to the cellar, but then I saw her look up and her face distorted into an expression of pure, undiluted terror. She covered her eyes with her hands and fell back into the kitchen as though she couldn’t bear to see what was coming. I looked up too.

And it was the strangest thing.

All of a sudden, everything seemed to stop. The screams, the rumbling, the crashing. It was as though a great peace had descended. There was a blinding light seemingly focused on us from somewhere very high up, as though we had been picked out by a theatrical spotlight. I saw raindrops swirling in the vortex like jewels. I was enraptured, frozen to the spot. Through the light and the whirling rain I was aware of a strange whooshing sensation that seemed to herald something approaching very fast. And I knew. I knew in a second of calm clarity what it was and that it was too late now to do anything. I held the boy close to me and bent over him as though shielding him from a sudden storm.

‘David,’ I whispered. ‘Hold tight, son.’

I’d been told that the survivors of the London Blitz had a saying: you don’t hear the bomb that’s coming for you. I was surprised, in those luminous seconds, to discover it was true.

*** A BBC2 BETWEEN THE COVERS BOOK CLUB PICK ***

*** BBC RADIO 4 BOOK AT BEDTIME ***

‘A fascinating, beautiful, heartwarming novel. It kept me gripped from the very first chapter’ — BETH O’LEARY

In Second World War Bath, young, naïve wireless engineer Will meets Austrian refugee Elsa Klein: she is sophisticated, witty and worldly, and at last his life seems to make sense . . . until, soon after, the couple’s home is bombed, and Will awakes from the blast to find himself alone.

No one has heard of Elsa Klein. They say she never existed.

Seventy years later, social worker Laura is battling her way out of depression and off medication. Her new case is a strange, isolated old man whose house hasn’t changed since the war. A man who insists his fiancé vanished many, many years before. Everyone thinks he’s suffering dementia. But Laura begins to suspect otherwise . . .

From Keith Stuart, author of the much-loved Richard & Judy bestseller A Boy Made of Blocks, comes a stunning, emotional novel about an impossible mystery and a true love that refuses to die.

‘Enthralling, a real thing of beauty. Dazzling’ — JOSIE SILVER

‘The Frequency of Us is a novel with a bit of everything: a sweeping love story, wonderfully complex characters, and a sprinkling of the supernatural. I loved it, and know it’ll stay with me for some time’ — CLARE POOLEY

‘A complete joy! An intelligent, intricate and emotive mystery’ — LOUISE JENSON