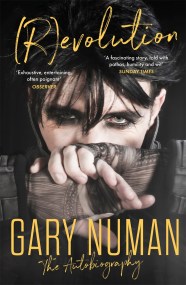

Start reading Gary Numan’s (R)evolution

Extracted from Chapter Two: 1970

Peer pressure is a very powerful thing, never more so than when you’re a teenager, but for some reason, almost certainly due to my Asperger’s, peer pressure has never really touched me. I am not swayed by any feelings of shame, or guilt, or a need to belong, nothing. When my friends would say you can’t hang out with us if you don’t smoke, I would move on. If they said you can’t hang out with us if you don’t drink, I’d move on.

Whatever it was, if I didn’t want to do it, I didn’t. I don’t do dares. A dare is just doing something stupid to amuse other people. Why would I want to do that? To belong? I don’t need to belong. I dare myself. I set my own challenges. Challenges that have meaning, that have purpose. I was therefore something of a loner. I followed my own path. I did things because I wanted to, or needed to, all part of a longer journey.

I sipped an alcoholic drink once, didn’t like it, saw no reason to persevere. I was witness to so many horrible examples of why drinking at a young age was not a good thing, or cool, that I had no interest in trying to ‘get a taste’ for it. Same with smoking.

A kid at school used to smoke, in the most exaggerated way, and he always looked to me like a little boy trying desperately too hard to be a man. It looked pathetic, and I never wanted to look desperate like that, to pretend to be something I wasn’t.

Actually be the thing you want to be, don’t pretend. During my last year at the grammar school, a careers lecturer made the point, incorrectly as it turned out, that ‘for those of you that dream of being a pilot, only one in a thousand ever achieve it’. The school had around a thousand pupils, and I was not the most academically accomplished, not by a long way, so with that terribly inaccurate career statement still ringing in my ear, I abandoned all thoughts of becoming a pilot. As far as I was concerned, the only thing left for me was being a pop star, and school had just become an even bigger obstacle.

For a while, after the Asperger’s revelation, I became very interested in trying to understand more about how the mind works, mine in particular. I read various books about mental health issues and, wherever possible, tried to find connections between the way I behaved, or felt, and the conditions I read about. I think part of it was a genuine interest in trying to understand what was going on, but a part of it was also a desire to simply believe that I was different. I wanted to be unique. It seemed necessary. I read about a thing called the disembodied self, a condition that means people are able to adopt an entirely different personality from one day to another. I tried that for a while and genuinely felt that I could do it. I would decide each morning what my personality was going to be for that day and be it. I wonder now, of course, if anyone else ever noticed, but it felt very real at the time. I also wonder why. What was the point? What was I hoping to achieve, whether I was successful or not? I tend to think it was just one rather odd way of trying to figure out what my personality really was, because I do believe it can be shaped, up to a point, while we’re still young.

At the end of my second try at the third year, I was expelled from Ashford Grammar and moved to Stanwell Secondary School, where, quite by accident, things got off to a very bad start. On my first day, trying to set a good impression, I arrived early and was one of the first into the assembly hall. I noticed a row of chairs at the back and genuinely thought it was a first come- first-served situation so sat down on a chair. But no, I’d committed a grave offence and was promptly marched away and given the cane. Before my first lesson had even started!

Every thought of keeping a lower profile was abandoned, and my time at Stanwell was a disaster from day one. But, this time, I don’t feel I was entirely to blame. Caning me, when I clearly had yet to learn the rules, was simply the school making a statement that they would take no shit from the newly arrived troublemaker. I understand their thinking now, but back then it was the worst thing they could have done and virtually guaranteed my time there would be filled with problems. My resistance to what I saw as unfairly handled authority, even at school level, became stronger. For example, the school uniform required a white shirt but, on one particular day, I didn’t have a clean one.

Not my fault. I chose the closest I had, a pale blue shirt, and went to school. During assembly, a teacher shouted at me, in front of everyone, ‘Look at the state of you, boy.’ I took great offence at that. I was clean, my clothes were fresh and ironed, and his comment seemed an insult to my mum, who made sure I at least arrived at school tidy. What made it worse, the teacher doing the shouting looked like a crumpled ragamuffin. So, with temper flaring, I replied, ‘Fuck me, look at the state of you,’ or something like that, and I was caned again. Sometimes, though, I was treated harshly through no fault of my own. As an example, our computer studies teacher failed to show up for one lesson, and the deputy headmistress came in and told us to get out our maths books. I raised my hand and told her it was a computer studies lesson. I honestly thought I was being helpful, but I got caned for that as well.

The thing that did bother me was the disappointment I saw in my parents when I was expelled from Ashford Grammar and the worry that my continued troubles at Stanwell caused them. I had been the bright shining star going towards a bright shining future when I started at grammar school, and I’d ruined it. Their pride in my grammar-school place had turned to a quiet embarrassment, coupled with a real concern about how I was progressing.

But even through all that disappointment, they allowed me to talk endlessly about my pop-star future, although I doubt they shared my confidence that it was guaranteed to happen. Looking back, the way I used to feel about it, speaking about it with such confidence, is a little embarrassing now. Today I’m far more aware, as my parents probably were back then, just how incredibly unlikely it is to ever achieve chart success, number 1 especially. But I think when you are younger, you do tend to look at your future as an endless opportunity, where all things are possible. I know I did. Again, I thank my parents for that. They made me feel that anything was possible – you just had to try, have faith in yourself and persevere.