Read an extract from The Running Vixen by Elizabeth Chadwick

The Welsh Marches, Autumn 1126

On the day Adam de Lacey returned to the borders after an absence of more than a year, the monthly market at Ravenstow was in full, noisy cry, and thus numerous witnesses watched and whispered behind their hands as the small but disciplined entourage wound its way through their midst.

The young man at the head of the troop paid scant attention to their interest, to the bustling booths and mingling of scents and stenches, the cries and entreaties to look, to buy – not because it was beneath him to do so, but because he was preoccupied and tired. As Adam rode past a woman selling fleeces and sheepskin winter shoes and jerkins, the lilting cadence of the Welsh tongue pleased his ears, causing him to emerge from his introspection and look around with a half-smile. Of late he had grown accustomed to heavy, guttural German, spoken by humourless men with a rigid sense of rank and order, their lifestyle the opposite of the carefree, robust Welsh, who had few possessions and pretensions and set very little store by those who did.

The outward journey to the mourning court of the recently deceased German Emperor had been filled with the violence and hardship of long days on roads that were often hostile, and the route home had been even worse owing to the querulous temper of his charge. Adam was an accomplished soldier, well able to look after himself where the dangers of the open road were concerned. The lash of a haughty woman’s tongue – and she the King’s own daughter and Dowager Empress of Germany – was a different matter entirely. Her high estate had prevented him from defending himself in the manner he would have liked, and the obligation of feudal duty had made it impossible for him to abandon her on the road, forcing him to bear with gritted teeth what he could not change; but then he was used to that.

A crone cried out to him, offering to tell his fortune for a quarter-penny. His half-smile expanded and developed a bitter quality. He flung a coin towards her outstretched fingers but declined to wait on her prophecy. He knew his future already – the parts that mattered, or had mattered once until time and grim determination had rendered them numb. Abruptly he heeled his stallion to a rapid trot.

Ravenstow keep, the seat of his foster father’s barony shone with fresh limewash on the crag overlooking the busy town. It had been built during the reign of William Rufus by Robert de Belleme, former Earl of Shrewsbury and now King Henry’s prisoner, his evil rule a fading but still potent memory; too potent for some who had lost their friends and family to the barbaric tortures he had practised in his fortress strongholds a generation ago.

Adam’s own father had been de Belleme’s vassal and accomplice, his name stained with the overspill from de Belleme’s infamies. Adam knew from servants’ tales, whispered in dark corners, the kind of man his father had been: a dishonourable molester of women and young girls, tarnished with murder and guilty of treason. Not an ancestor to claim with pride, but one to bury deep with guilt and shame.

The drawbridge was down but the guards on duty were swift to challenge him, and only rested their spears when they had taken a close look at his banner and the face revealed to them as he removed his helm by its nasal bar. Then they let him pass with words of greeting on their lips, and speculation rife in their eyes.

Eadric, the head groom, emerged from the stables to take the dun and deployed his underlings among Adam’s men. ‘Welcome, my lord,’ he said with a half-moon grin.

‘It has been a long time.’

Having dismounted, Adam stared around the busy bailey which looked just as it always had. The smith’s hammer rang out clear and sweet from the forge against the curtain wall. A soldier’s woman was tending a cooking pot tripoded over an open fire, and the savoury steam

drifted tantalisingly past his nostrils, reminding him that he hadn’t eaten since well before prime. Hens pecked underfoot, doves from Countess Judith’s cote cooing and pirouetting among them. A curvaceous serving girl carried a tray of loaves across the ward and was whistled at by a group of off-duty soldiers playing dice and warming their backs against a sunny timber wall.

‘A long time, Eadric,’ he agreed, with a sigh and a wary smile. ‘Is Lord Guyon here?’

‘Out hunting, sir, and the lady Judith with him.’ Eadric looked apologetic, and then brightened. ‘Master Renard is here though, and Mistress Heulwen.’

The smile froze upon Adam’s face. He set his hand to his stallion’s reins as though he would mount up again, but then glanced round at his men. He could hear their groans of relief and see the way they stretched stiff muscles and rubbed sore backs. They were tired, having ridden a bone-jarring distance, and it would be foolish and grossly discourteous to ride out now that their presence was known.

A young man with a stork’s length of leg came striding towards him from the direction of the mews, stripping a hawking gauntlet from his right hand as he advanced. He had pitch-black hair and strong features just beginning to pare out of childhood’s unformed roundness. It

took Adam a moment to realise that this was Renard, Lord Guyon’s third son, for when last encountered the lad had been a lanky fourteen-year-old with less substance than a hoe-handle. Now, although still on the narrow side, his limbs were beginning to thicken out with pads of adult muscle and he moved like a young cat. ‘We thought you’d gone for good!’

Renard greeted Adam with a boisterous clasp on the arm and a total lack of respect. His voice was husky and a trifle raw, revealing that it had but recently broken.

‘So did I, sometimes,’ Adam answered wryly, and took a step back. ‘Holy Christ, but you’ve grown!’

‘So everyone keeps telling me – but not too old for a beating, Mama always adds!’ Renard laughed merrily displaying white, slightly uneven teeth. ‘She’s taken my father hunting because it’s the only way she can get him to relax his responsibilities for a day, short of spiking his wine – and she’s done that before now. There’s only myself and Heulwen here. She’ll be right glad to see you.’

Adam lowered his gaze. ‘Is her husband here too?’

They went up the forebuilding steps and entered the great hall. Sweet-scented rushes crackled underfoot, and sunlight shone through the high window spaces and illuminated the embroidered banners adorning the walls. Renard bade a servant bring wine, then tilted his visitor a speculative look from narrow, dark-grey eyes. ‘Ralf was killed at midsummer by the Welsh.’

‘God rest his soul.’ Adam crossed himself, the words and gesture emerging independent of his racing mind.

Renard grimaced. ‘It was a bad business. The Welsh have been biting at our borders like breeding fleas on a dog’s back ever since it happened. Warrin de Mortimer chanced on the attack, drove the Welsh off and brought what was left of Ralf home. Heulwen took it badly. She and Ralf had quarrelled before he rode out, and she blames herself.’

The maid approached them with a pitcher and two cups, her eyes flickering circumspectly over Adam. He stared through her, a muscle bunching and hollowing in his cheek. The wine was Rhenish, rich and smooth, and he almost retched, remembering Heulwen’s wedding day

and how he had drunk himself into a stupor on this stuff and Lady Judith had forced him to be sick in order to save his life. Afterwards, the incident had faded into a memory recalled with wry chuckles by everyone except himself. Sometimes he wished that they had been sufficiently

charitable to let him die.

Renard sat down on a fur-covered stool before the hearth, dangled his cup between his knees and said disgustedly, ‘De Mortimer’s been buzzing around Heulwen like a frantic wasp at an open honey jar. It’s only a matter of time before he formally asks my father for her.’

‘Is he likely to agree?’

Renard jerked his shoulders as if ridding them of something that chafed. ‘Admittedly it’s a useful bond, and as Warrin was once one of my father’s squires, he’ll probably get a generous hearing.’

Adam filled his cheeks with the wine, then swallowed it. He remembered the rasp of dust against his teeth, the sensation of a spur-clad heel grinding on his spine, a mocking voice telling him to get up and fight. The bruises, the humiliation, the tears swelling painfully in

his throat and choked down by fear of further scorn; the effort to rise and face his adversary, knowing he would be knocked down again. Training, it was called: a thirteen-year-old facing a man of twenty, whose sole concern was to display his superiority and put the most junior squire firmly in his place. Oh yes, he well knew the glorious Warrin de Mortimer.

‘And Heulwen herself ?’ he asked with forced neutrality.

‘Oh, you know my sister. Playing hard to get as only she can, but I think she might have him in the end. Warrin offered for her before, you know, but was turned down in favour of Ralf.’

‘And now Ralf ’s dead.’

‘Yes.’ Renard cocked him a curious look, but something in Adam’s manner made him change the subject. ‘What’s Matilda like?’

Adam gave him a rueful look. ‘That would be the “Empress Matilda”,’ he said. ‘Woe betide anyone who doesn’t afford her the full title. She’s as cold and proud as a chunk of Caen stone.’

‘You don’t like her then,’ Renard said with interest. ‘I didn’t get close enough to find out – I didn’t want to end up as stone too!’

The younger man grinned over the rim of his goblet. ‘It’s no cause for laughter, Ren. Henry hasn’t just summoned her home to comfort his dotage or her widowhood. She’s to be our future queen, and when I see her treating men like dirt under her feet, it chills me to the marrow.’

‘Just how did you end up in the entourage sent to fetch her?’ Renard asked.

Adam smiled darkly. ‘I’ve served at court, so I suppose Henry knows I’m discreet and stoical – unlikely to boil over in public at being called a mannerless oaf with mashed turnip where my brains should be.’

‘She said that to you?’ Renard bit his lip in an unsuccessful effort to conceal his mirth.

‘That was the least of her insults. Of course, most of them were in German, and I didn’t ask to have them translated. Even a mannerless turnip-brain has his pride. I—’ He stopped and stared across the hall, suddenly transfixed.

Heulwen stood in a shaft of sunlight that fired her braids beneath the simple white veil to the precise colour of autumn oak leaves. Her russet wool gown was laced tightly to her figure, and as she approached the hearth the delicate gold embroidery at the throat and hem of the

dress glittered with trapped light.

Adam closed his eyes to break the contact, swallowed, and prepared to endure. He would rather a hundred times over have undergone the haughty scorn of the Empress Matilda than face the woman who approached him now: Heulwen, Lord Guyon’s natural daughter out

of a Welsh woman whom his own father had murdered during the dispute for the crown more than twenty-four years ago.

He rose clumsily to his feet and some of the wine slopped down his surcoat, staining the blue silk. He could feel his ears burning and knew he had coloured like a gauche youth.

‘Adam!’ she cried joyfully, and with complete lack of self-consciousness flung her arms around his neck and drew his head down to kiss him full on the lips. The scent of flowers engulfed him. Her eyes were the colour of sunlit sea-shallows – azure and aquamarine, flecked with mica-gold. His throat tightened. No words came, only the thought that the Empress’s remarks were perhaps not insults but the truth.

Heulwen released him to step back and admire the new style of surcoat he wore over his hauberk, and the ornate German swordbelt. ‘My, my,’ she teased, ‘aren’t you a sight for sore eyes? Mama will be furious to have missed greeting you. You should have sent word on

ahead!’

‘I was in half a mind to ride to Thornford first,’ he said in a constricted voice, ‘but I have a letter to your father from the King.’

‘Churl!’ she scolded, eyes dancing. ‘It’s fortunate that some of us are not so lacking in courtesy. There’s a hot tub prepared above.’

Adam stared at her in dismay. He was accustomed to bathing at least once in a while. Indeed, he enjoyed the luxury and relaxation it provided, but he was filled with dread, knowing that Heulwen, as hostess, would be responsible for unarming him and seeing to his comfort.

‘I haven’t finished my wine,’ he said woodenly, ‘or my conversation.’

Renard said unhelpfully, ‘You’ll only have to repeat it all later to my parents, and there’s no law against taking your wine upstairs.’

‘And since I have gone to the trouble of preparing a tub, the least you can do is sit in it. You stink of the road!’ It was hardly the way to speak to a welcome guest, and Heulwen could have bitten her tongue the moment the words emerged. Since Ralf ’s death she had found herself being irritable and snappish. People made allowances – those who knew her well – but it was a

long time since she and Adam had shared the closeness of childhood friendship.

Adam stared obdurately at the wall beyond her head, refusing to meet her eyes. ‘Well that’s because I’ve been on it for a long time – too long, I sometimes think.’

She touched him again with eyes full of chagrin.

‘Adam, I’m sorry. I don’t know why I said such a thing.’

‘Because you have gone to the trouble and I am not suitably grateful?’ he replied with a grimace that just about passed for a smile. ‘Well if I am not, it is because I’ve had a crawful of being ordered around by a woman.’ ‘Straight to the middle of the target!’ crowed Renard

at his blushing half-sister.

‘No insult intended in my turn.’ Adam put down the cup which was still more than half full of wine, and went towards the curtain that screened off the tower stairs. ‘Bear with me awhile until I’ve found the grace to mellow.’

‘Jesu,’ Renard said to her with a shake of his head.

‘He hasn’t changed, has he?’

Heulwen looked baffled. ‘I don’t know. When I mentioned the bath, I thought he was going to turn tail and flee.’

‘Perhaps the Germans mutilated him below,’ Renard offered flippantly, then shot her a shrewd glance. ‘Or perhaps they didn’t.’

Renard was like that. The unwary were lulled into seeing a likeable, shallow youth, wallowing through the pitfalls of adolescence towards a far-distant maturity, and then he would suddenly shatter that assessment with a piercing remark or astute observation far beyond his

years.

‘Then he’s a fool.’ Heulwen tossed her head. ‘I’ve bathed enough men in courtesy to know what sometimes happens if they’ve been continent for too long. I won’t be embarrassed.’

‘No,’ Renard quirked his brow, ‘but he might.’

'An author who makes history come gloriously alive'

The Times

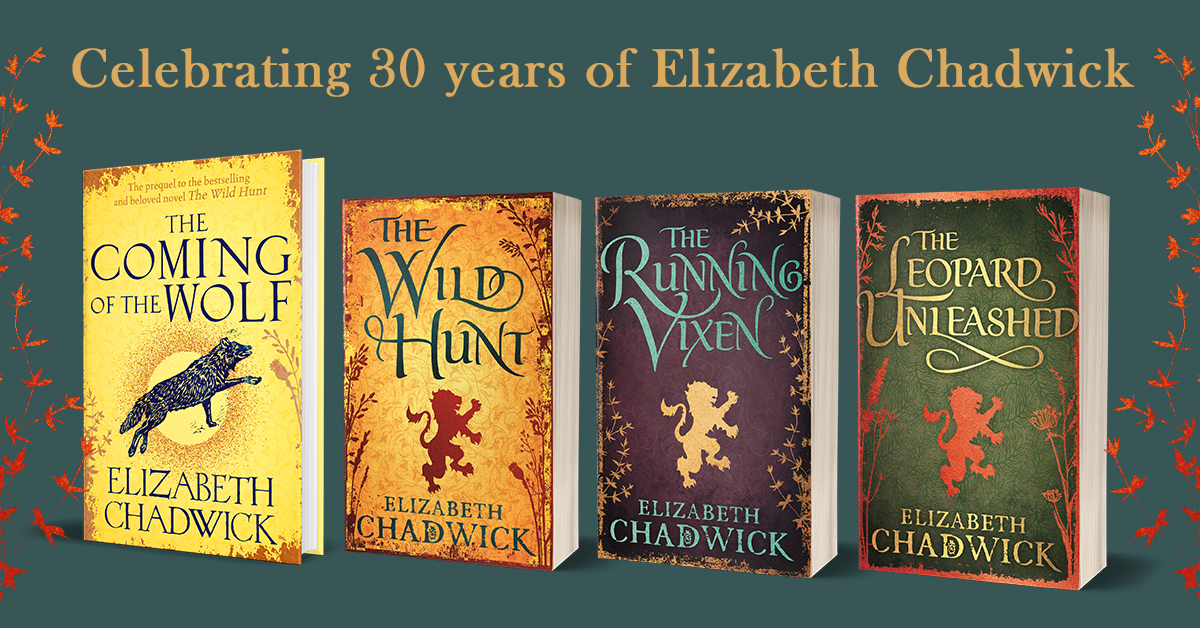

Elizabeth Chadwick's bestselling, award-winning first novel, and the start of the beloved Wild Hunt series.

In the wild, windswept Welsh marches a noble young lord rides homewards, embittered, angry and in danger.

He is Guyon, lord of Ledworth, heir to threatened lands, husband-to-be of Judith of Ravenstow. Their union will save his territory - but they have yet to meet...

For this is Wales at the turn of the twelfth century. Dynasties forge and fight, and behind the precarious throne of William Rufus, political intrigue is raging.

Caught amidst the violence are Judith and Guyon, bound together yet poles apart. But when the full horror of war crashes over Guyon and Judith, they are forced to face insurmountable odds. Together...

Winner of the Betty Trask Award

*

'Picking up an Elizabeth Chadwick novel you know you are in for a sumptuous ride'

Daily Telegraph

'Meticulous research and strong storytelling'

Woman & Home

The beloved second book in The Wild Hunt series: stunning historical detail, beguiling characters and superb storytelling.

A forbidden love takes England to the brink of war...

1126. Heulwen, daughter of Welsh Marcher baron Guyon FitzMiles, has grown up with her father's ward, Adam de Lacey.

There has always been a spark between them, but when Heulwen marries elsewhere, a devastated Adam absents himself on a diplomatic mission for King Henry I.

When her husband is killed in a skirmish, Heulwen's father considers a new marriage for her with his neighbour's son, Warrin de Mortimer. Adam, recently returned to England, is determined not to lose Heulwen a second time.

But Heulwen is torn between her duty to her father and the pull of her heart. Adam is no longer the awkward boy she remembers, but a man who stirs every fibre of her being - which places them both in great danger, because Warrin de Mortimer is not a man to be crossed and the future of a country is at stake . . .

*

Praise for Elizabeth Chadwick

'An author who makes history come gloriously alive'

The Times

'Picking up an Elizabeth Chadwick novel you know you are in for a sumptuous ride'

Daily Telegraph

'Meticulous research and strong storytelling'

Woman & Home

'Meticulous research and strong storytelling'

Woman & Home

The heart-pounding end to The Wild Hunt series: stunning historical detail, beguiling characters and superb storytelling.

Renard, heir to Ravenstow, is a crusader far from the cold Welsh Marches of his birth.

Summoned home to his ailing father, Renard brings Olwen with him, an exotic dancing girl. Yet, in a political match made by their families, Renard is already betrothed to the innocent Elene and he knows he is returning to the duty of marriage.

Torn between Olwen and Elene, Renard's personal struggle is set against a background of increasing civil strife as Ranulf of Chester, his greedy neighbour, strives to snatch his lands. When Renard is taken prisoner at the Battle of Lincoln, his fate is placed in the hands of the two women - his former mistress, now in the bed of his deadliest enemy, and his determined yet inexperienced wife, protecting his lands against terrible odds . . .

*

Praise for Elizabeth Chadwick

'An author who makes history come gloriously alive'

The Times

'Picking up an Elizabeth Chadwick novel you know you are in for a sumptuous ride'

Daily Telegraph