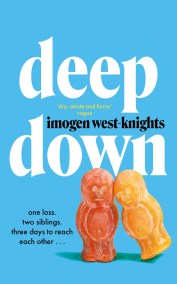

Read an extract from Deep Down by Imogen West-Knights

1

She drops her suitcase on an old woman’s head. As it begins to tip out of the overhead locker, Billie realises that her arms aren’t going to be strong enough at this angle to stop it from slipping out of her grasp. She only manages to say the words ‘watch out’ after the bag has hit the woman, and the sound it produces as one hard corner makes contact with her skull is appalling. The woman, who had been sitting quietly when the suitcase fell, is now bent over herself, clutching her head and making a series of distressing noises.

‘I’m so sorry, I’m so sorry,’ Billie says, panic rising in her chest as she feels the aura of threat radiating from passengers five rows deep in front and behind. The woman’s husband gets to his feet as fast as his joints will allow and bends over her, one hand on his wife’s back and the other raised in open- palmed fury towards Billie.

‘What the hell is the matter with you?’ he asks, and she hears his question echoed in mutters by the other passengers.

‘What’s the fucking hurry? Look what you’ve done. Look at what you’ve done to her.’

Billie looks at what she’s done and feels her voice get tighter and tighter as she continues to apologise. What is the matter with her? It’s a question she doesn’t have an answer to. They had been waiting on the tarmac for about twenty minutes when she decided to reach over the elderly couple behind her and retrieve the wheelie bag. There hadn’t been space to stow it above her own seat before take- off, and once the doors opened she didn’t want to hold people up by having to go against the flow to fetch it. Clearly now, the right thing would have been just to wait, and go back up the plane to get her bag once everyone else had disembarked. There was no hurry. She feels heat spread up her neck and she begins to cry.

‘I don’t know what you’re crying for,’ a woman, seemingly unconnected to the victim, says. ‘She’s the one who should be crying.’

The elderly woman is, in fact, crying a little.

‘I’m sorry,’ Billie tries one more time, this apology for the crying as much as the woman’s head. ‘My dad just died.’

The unconnected woman gives her an exasperated look, one that seems to ask what she is supposed to do with this information. Immediately, Billie knows that this is a cheap trick. She feels its cheapness ripple through the onlookers, who continue to tut and talk about her in the third person amongst themselves. What she said happens to be true, but it is difficult to connect it to this incident with the suitcase. Still the plane doors remain closed. An aghast flight attendant is now fighting his way past the people standing in the aisle.

When he reaches the woman, he begins to administer the contents of a first aid kit.

‘I’m so sorry,’ Billie says to the flight attendant, desperate to endear herself to somebody, and he gives her a nod of professional neutrality. The woman appears to be bleeding. Billie stands with her eyes pinned to the floor and tries in vain to induce an out- of- body experience.

After a long time, colder air touches her face and tells her that the doors are open. Billie considers turning around to offer a final apology to the woman, who is now telling the flight attendant exactly which elements of her holiday this injury will prevent her from participating in, but she doesn’t find the courage to do so. She shuffles out, dragging the suitcase behind her like a disgraced dog on a leash, clambers down the steps onto the tarmac and walks directly to the toilets to cry properly. After she is done, she sits on the toilet seat and waits until she thinks she’ll be the last person from her flight in arrivals. She tips the suitcase onto its side in the cramped space of the cubicle to examine the corner for evidence of impact, but she can’t find any.

The concourse is busy and Billie looks around in the vain hope that her brother has come to collect her, even though that isn’t what they’ve arranged. She finds a quiet corner to check her phone for the directions Tom sent and to take a few steadying breaths. Twelve stops, her brother had said, on the blue line to Châtelet, and then a five- minute walk. She reads the text again to be sure she remembers it, and then also reads the follow- up text in which he had explained that Châtelet means ‘little castle’. She hadn’t known what she was supposed to make of this detail, and so had sent a thumbs- up emoji back. There is a map on the wall next to her, which she consults. It’s colourful with lines like the ones back in London, but numbered rather than named. Once she feels confident of the route, Billie weaves her way through the families and couples to buy a ticket.

Underground, she boards a packed train, and tries to reach up for the handrail at the same time as pulling down her top to contain the patch of stomach that the reaching reveals. She has a plain, mashed potato sort of a face, but it appears even more washed out than usual in the scuffed window of the train door. Sometimes when she looks at her reflection, she can see it spreading out at the edges like batter on a pan. It doesn’t especially bother her. The original face wasn’t all that special, if the face she left school with even was the original face. She believes that women’s faces exist on a bell curve, from not quite ready up to the peak of their true, adult face, and then a slow deterioration into the faces of old age. But she doesn’t know where the top of that bell curve is, for her. It’s likely that she won’t realise when she’s there, and then she’ll have missed it completely. At each station her face disappears from her view as a passenger uses a lever to throw the doors open a second or so before the train has stopped. She wonders whether this is actually dangerous or just looks it.

She receives a text.

Just asked and I can leave at 22. Meet you at the flat

She reads it twice, and wonders why he doesn’t just say 10 if he means 10, then hopes it isn’t a typo for 12.

When Billie emerges out into the city, she finds it humming with early evening energy. There is something alive in the air that makes her exhaustion more acute by contrast. She feels conspicuous on the walk to the flat, scrutinising the directions with her phone held out in front of her and pursued by the growl of her suitcase wheels.

The door into her brother’s building closes behind her with a rusty screech and slam. Tom’s flat is on the top floor, and as Billie heaves her bag up the stairs, she listens to her labouring footsteps echo in the stairwell. Outside his door, she lifts a scruffy mat and finds the key. It takes some jiggling in the lock, as he’d said it would, and when the heavy door swings open she follows its momentum until she is standing inside the room. Billie looks around, turning a full circle in the tiny space. She opens a door to her right, to see if there is more apartment hidden away, but it’s a cupboard that contains one suit, looking like a hanged man. The shower, the hob, the bed, the sink and a small table could all be reached by stretching out a limb from the centre of the room. There is a set of French windows and six inches of balcony space that looks out onto a courtyard. A choppy sea of grey metal rooftops stretches out, and the spires of various churches interrupt the sunset beyond.

This spartan, ill- decorated room makes Billie think of her brother as young, which is not something she’s used to doing. Four years older than her, his age has always seemed massive, almost stately. Now, though, she looks at where he lives and recognises that they’re at more or less the same stage of life, trudging through the featureless landscape of being twenty- something. It’s a strange, un- mooring sensation.

The time is glaring in red from an alarm clock on the edge of the table. Tom won’t be home for two hours. She pictures herself drinking a glass of white wine alone in a Parisian bar, wearing some kind of pashmina shawl her suitcase doesn’t contain. The image strikes her as tragic. She’ll wait for him here.

The tuna wrap she had bought at the airport but been too embarrassed to eat on the flight has gone moist and is sagging in a way that reminds her of skin. It’s unappealingly warm but she eats it anyway, lingering over each wet mouthful to pass the time. Then she finds herself poking around the little room. Tom’s bed is a futon on some pallets, which have partially collapsed, leaving the mattress to slope towards the floor at one corner. She recognises very few of his possessions. There’s a toy pig their aunt gave him when he was small, an ugly sort of knitted hoodie he brought back from some music festival, a slumped matte wash bag. But everything else is unfamiliar. He owns eight books, and she doesn’t recognise any of their names. They look like novels, and some are in French. She flicks through one of them, its margins occasionally marked with scribbled stars, and puts it back where it was. There is a diary that Billie is both tempted to read and a little repulsed by the thought of reading. She opens it a crack, but all it contains are appointments, the odd password and username.

Even though the room is tiny, there are few enough things in it to make it feel sparse. Tom has always had a talent for shedding things rather than acquiring them. Over the back of a schoolroom wooden chair, he has one of the same IKEA blankets that Billie and everybody she knows owns, except his still has the large, papery care label on it. She rips it off absent- mindedly, gathers up the packaging from her wrap and discovers a plastic bag hanging sheepishly off the cupboard door beneath the sink instead of a bin. Adrift in the middle of the largest wall there is a very small, framed line drawing of a village in England Billie is not aware of his ever having been to.

The room is cold, although the day outside is not. By the hob, there are teabags in a crushed cardboard package next to a hunk of baguette. Billie makes herself a cup of tea that is crunchy with limescale. Once she’s established that there is definitely not a bathroom secreted anywhere in here, she goes exploring back in the hallway. Halfway up the next flight of stairs she finds one, although it also seems to be some kind of storage space. Sat on the toilet, wedged between a bouquet of broom handles and a broken- looking coffee machine, the image of her suitcase hitting the woman flashes before her and she lets out a pained, involuntary whimper.

Back in Tom’s room, Billie inspects the bed. She decides it’s relatively clean, and so she gets in under the covers. If she squashes herself flush with the wall, the sag isn’t too noticeable. She gets her laptop out, puts on Ocean’s Eleven and falls asleep very quickly.

Tom turns his key in the lock and opens the door. Inside, he finds the darkness punctuated only by Billie’s face, illuminated by the screen, her mouth hanging slightly open as the tinny sound of heist music plays. He smiles and takes a picture to show her in the morning. He is tired and relieved not to have to entertain her until then. It’s early enough, but he might as well go to bed too. Tom changes out of his work clothes quietly, hanging them over the balcony to air out the beer and ketchup smell, and unrolls a yoga mat and a sleeping bag. He manoeuvres himself inside the bag, leans over to extract one of the thin, flat pillows from under Billie’s head and then shuts the laptop.

‘What?’ mumbles Billie.

‘Go to sleep.’

She makes a low noise in reply, and he hears her shuffle to face the wall. Tom lies awake for a while, his eyes tracing the familiar contours of the ceiling, just about visible in the dark.

Deep Down

by Imogen West-Knights

A 2023 best book to look forward to in Vogue, Bustle, GQ and the New Statesman

'A superbly observed exploration of intimacy and its failings' Megan Nolan

'West-Knights is a masterful, hilarious and humane story-teller' Olivia Sudjic

'A sharp and clear-eyed portrait of familial love and the ways it makes us mad' Monica Heisey

Billie and Tom have just lost their father. It should be a time to comfort each other, but there's always been a distance to their relationship. Determined to change this, Billie boards a flight to her brother in Paris.

Dazed by grief, the siblings spend days wandering the streets, both helping and hurting each other in the process. When their explorations lead them to the infamous Paris catacombs, they will finally be forced to face the secrets lurking in their past that illuminate the questions in their present.

Funny, moving and unexpected, DEEP DOWN is an empathetic and hard-hitting look at both the struggles and the joys of sibling relationships, and the realities of grieving the loss of someone who was already an absence.