The Human Stories Behind The Fourth Shore

A century ago, when Italy was trying for the second time to expand its colonial reach, several thousand Libyan men who resisted Italian rule were deported. They were shipped to small islands off the coast of Sicily, there to live out their days. Little is known about them. No lists were kept (or made?) of subjects who left Libya, and an unspecified number died during the crossings, making it difficult to estimate exactly how many there were. Mass deportations stopped in the fascist era (1922 to 1943) when home-based concentration camps replaced the practice.

In the twenties and thirties, the islands of Favignana, Ustica, Tremiti and Lipari were used as prisons for anti-fascist dissidents and homosexuals by the Mussolini regime. Some of those internal exiles commented on the forlorn Libyan men, squatting on the cliff-tops in their tattered white robes, looking out to sea, forever hankering after their homeland.

Back home in Libya, they were referred to as the souls lost on Italian soil.

As far as I know, no books have been written specifically about them and they have rarely been the subject of scholarly investigation. They were merely taken to the rocky islands around Sicily or, later, to the island of Sicily itself, never to return. The largely untold story of these deportees became the spark that ignited my novel, The Fourth Shore – as much for the silence around their fate as for its unsung poignancy.

Archive of the Centro Studi e Documentazione Isola di Ustica.

In this photograph showing the arrival of a few dozen of them on the island of Ustica in 1911, some of the Italian officials have been touched up in bold so that they stand out solid and black, while the Libyans sit pale and ghostly on the shore, already fading away – reinforcing the notion of where the power lay and who the masters were, had it been in doubt.

The trace these lost souls leave in The Fourth Shore is also faint but their story imbues the whole because it captures the inequality of the opposing forces – who counts and who barely registers – and the extraordinarily disempowering and nullifying effect of the silence that surrounds their fate. In fact, not just this early part but the whole period of the Italian colonization of Libya (1911 to 1943) is so little known or discussed as almost to constitute a secret. Censorship during the fascist period ensured (more or less) that only the information the authorities wanted known emerged. Later, the loss of all Italy’s colonies in the Second World War meant that the past was considered already over, without any need to understand it, to learn from it or apply its lessons. It is therefore no surprise that secrets and lies lie at the heart of my story.

The version of Italian Libya that the fascist regime wanted to show was of glamour, modernity, new developments, innovative architecture and model villages in a peaceful country where the local population had ‘submitted’. The concentration camps in the Cyrenaica desert in which up to 80,000 people died and the mustard gas bombing campaigns were not public knowledge. Propaganda focused on the international trade fair, the roads and churches, manufacturing, palaces and gracious squares and, above all, the Tripoli Grand Prix.

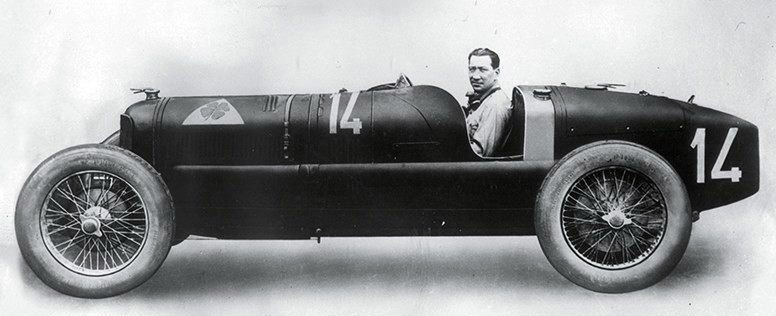

The Grand Prix epitomized Italy’s vision of the colony. It was glamorous and cutting edge and the racing drivers were famous and feted, the film stars of their day. Where they went, the money went. Count Gastone Brilli-Peri, nicknamed ‘Gastone the African’ because he loved racing in Libya so much, won the race in a Talbot in 1929 and died on the Tripoli race track in 1930.

Gastone Brilli-Peri

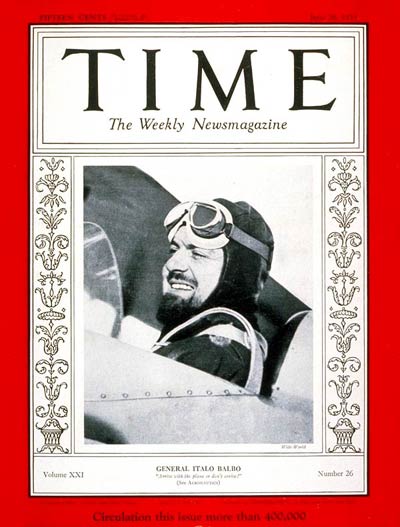

By the mid-thirties the Tripoli race was one of the fastest and richest in the world, and each year the governor general of the colony hosted a ball to celebrate it in his gold-domed palace. The governor general in question was the dashing and charismatic Italo Balbo – a real life figure who helped inspire my fictional world and provided one of the models for a certain kind of man – personally brave, physically strong, handsome, brutal and entitled.

Balbo was a controversial fascist party official with a murky past as a political thug but also the hero who flew solo across the Atlantic. A man of great swagger and derring do. The picture shows him on the cover of Time magazine after his solo flight when he became the darling of America.

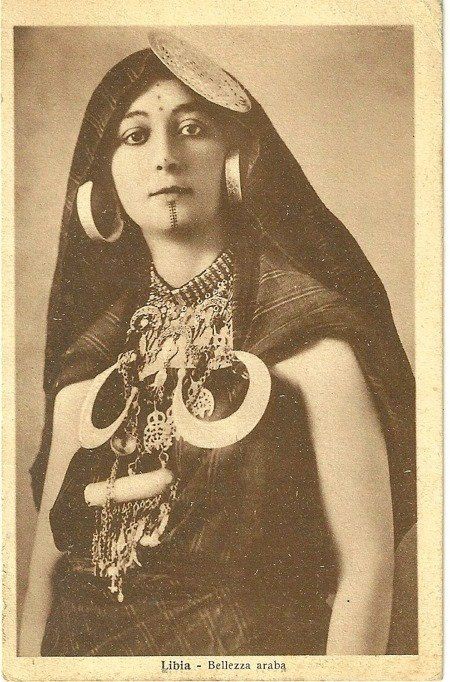

On the Libyan side – fittingly, given the absence of available information and records – an unnamed local girl pictured on a contemporary Italian postcard, captioned ‘Arab Beauty’ inspired the creation of my character Farida, a Bedouin girl from a desert town in Cyrenaica. Her story unfolds through her relationship with my protagonist Liliana, a child of fascist Italy. These two young women’s lives intersect, and are changed as a result, but it is Farida who uses what little agency she has, setting an example that blinkered Liliana struggles to follow.

In revisiting and attempting to bring to life the colourful, sad and complex reality of the colony, I was painfully aware both that writing about the past is always a way of writing about the present and that secrets can have a corrosive effect. It is unsurprising that those few historians who have investigated this period question what contribution the silences and the wilful amnesia have made to the present-day democracy deficit.

The Fourth Shore is out now. Click here to find out more.