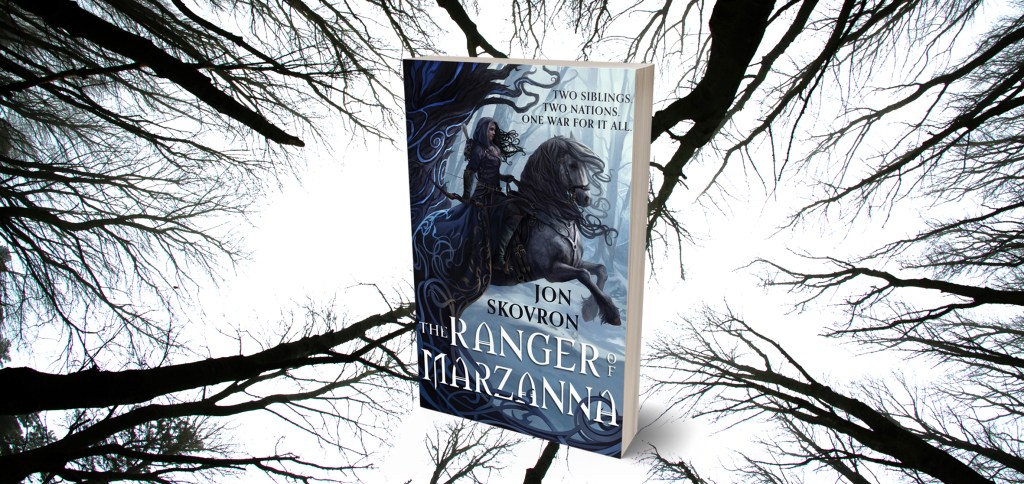

The Solitary Hero by Jon Skovron

Ah, the ranger. We know what that is, right? Whether it’s Aragorn in Lord of the Rings, Benjen Stark in The Song of Ice and Fire, or the classic adventuring class in Dungeons & Dragons, rangers are a staple of fantasy stories. They generally have a bow, and they know stuff about nature, both of which are really handy for an adventuring party if you’re traveling through a forest.

But is that all a ranger is in fantasy stories? The archery and nature person?

According to Merriam-Webster, a ranger can be defined as:

1a : the keeper of a British royal park or forest

1b : FOREST RANGER

2 : one that ranges

3a : one of a body of organized armed men who range over a region especially to enforce the law

3b : a soldier specially trained in close-range fighting and in raiding tactics

I particularly like #2. In the same way that a writer can be defined simply as “one who writes”, a ranger is ultimately just “one who ranges.”

Now as for what we mean by “ranges”, Merriam-Webster offers many definitions, but this is the pertinent one for us:

1a : to roam at large or freely

2b : to move over an area so as to explore it

So a ranger is someone accustomed to roaming freely over a large area of unexplored land, during which time they probably have little contact with others. Because of that, it seems essential that a ranger must grow accustomed to solitude.

Perhaps unsurprisingly given the state of the world during this global pandemic, I’ve been thinking about solitude a lot lately. And when I think about solitude, my mind often turns to the german poet, Rainer Maria Rilke. He had a lot to say on the subject in his Letters to a Young Poet.

First, he insisted that solitude was important:

”The necessary thing is after all but this; solitude, great inner solitude. Going into oneself for hours meeting no one – this one must be able to attain.”

But he did not deny that it could be difficult.

”Embrace your solitude and love it. Endure the pain it causes, and try to sing out with it.”

Ultimately, he believed that once you had embraced solitude and learned to love it, it would eventually be a comfort to you:

But your solitude will be a support to you and a home for you, even in the midst of very unfamiliar circumstances, and from it you will find all your paths.

Henry David Thoreau also had his fair share of thoughts on the value of solitude:

”The man who goes alone can start today; but he who travels with another must wait till that other is ready.”

He also saw that it was not always something that society looked kindly upon:

”If a man does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer. Let him step to the music which he hears, however measured or far away.”

There may be a temptation, particularly for Americans like myself, to lump the ranger into that classic Hemingway ideal of rugged individualism. But if you’ll pardon the archery pun, that somewhat misses the mark. Solitude does not mean self-absorption, and preferring to be alone does not mean indifference to others.

In their solitary wandering, rangers find a deeper connection to the world around them. That’s where the “nature stuff” comes in. I imagine that such a deep connection allows them to see a bigger picture. They understand that what affects one person, affects everyone. Because of that, there is a sense that their justice is above petty politics and the whims of individuals. They represent the law of nature itself.

More modern stories tend to focus on the third definition of a ranger: “one of a body of organized armed men who range over a region especially to enforce the law”. The Lone Ranger (who was never actually alone), Walker, Texas Ranger (aka Chuck Norris), and even the Mighty Morphin Power Rangers all fit that description. I suspect the reason the definition shifted for a modern context is because, well, there isn’t really any more ranging to be done. We’ve mapped the world. There’s no forest left to discover, no mountain that hasn’t already been climbed. Even if you’ve never been to a place, your phone can usually tell you how to get around.

Now, that’s not a bad thing, certainly. Science is cool and it’s good to know how to get around. But perhaps the reason rangers have so much allure these days is because they help us imagine, if just for a little while, wandering a world shrouded in mystery, with the potential for new and unimagined beauty lurking just over the next rise.

Read Jon’s new book, The Ranger of Marzanna, now!